Gail Dubrow is in the vanguard of a new mainstream that was, just a generation ago, very much on the margins. A social historian of the built environment and cultural landscape, she credits UO for leading her to a career that has raised public awareness of the history of American women, ethnic communities, LGBT communities, and other underrepresented groups by documenting and protecting places significant to their heritage.

Hers wasn’t a direct route, nor was it easy. But it has been satisfying. “It wasn’t that fun at the beginning—to be ignored, then ridiculed, then fought viciously,” she says, surprisingly with a hearty laugh. Dubrow founded the Preservation Planning and Design Program at University of Washington and served as vice provost and dean of the Graduate School at University of Minnesota, where she now teaches. She is author of two award-winning books, Restoring Women’s History Through Historic Preservation, and Sento at Sixth and Main: Preserving Landmarks of Japanese American Heritage.

A&AA interviewed Dubrow when she was on campus to accept the Lawrence Medal in 2015. Here are highlights of that interview:

Q: The Lawrence Medal selection committee appreciated that you helped to trailblaze the concept of cross-disciplinarity. Was there a single A-ha! moment when you realized you could integrate your various areas of study, or did things more gradually fall into place?

A: Like a lot of young people—I went to college at 17—I knew I had certain passions and they didn’t all come together clearly in any way I could see. I had always been interested in literature and I wanted to write, and I was talented in the visual arts and took night and weekend classes [in those subjects]. I had an uncle who was an architect and I saw some models in his apartment; he wasn’t a mentor but I had an eye. My junior year I took a summer program at Parsons School of Design that exposed me to all the different arts. One week Kevin Roche took us out to the Ford Foundation building and it fascinated me, oh my god it fascinated me. It was something about the way in which he had designed materials so they would rust over time, they’d get that patina, and it had a very big open atrium at the center with a lot of landscaping inside and the offices all looked on a common space. It was an early effort to create a sense of openness right in the heart of the city. It just got me. It’s not that I would ever design in that style, it was just this idea that so many different ways of thinking, viewing, art, and science—the ideals of what architecture could be as an integrated field—just struck me. And that’s when I knew I would head to architecture school.

A: Like a lot of young people—I went to college at 17—I knew I had certain passions and they didn’t all come together clearly in any way I could see. I had always been interested in literature and I wanted to write, and I was talented in the visual arts and took night and weekend classes [in those subjects]. I had an uncle who was an architect and I saw some models in his apartment; he wasn’t a mentor but I had an eye. My junior year I took a summer program at Parsons School of Design that exposed me to all the different arts. One week Kevin Roche took us out to the Ford Foundation building and it fascinated me, oh my god it fascinated me. It was something about the way in which he had designed materials so they would rust over time, they’d get that patina, and it had a very big open atrium at the center with a lot of landscaping inside and the offices all looked on a common space. It was an early effort to create a sense of openness right in the heart of the city. It just got me. It’s not that I would ever design in that style, it was just this idea that so many different ways of thinking, viewing, art, and science—the ideals of what architecture could be as an integrated field—just struck me. And that’s when I knew I would head to architecture school.

But I did not want to give up the reading-writing part of things so that’s why I came here, knowing I would study more than one field. I purposely picked a place where you could get multiple degrees, where I didn’t have to give something up to select a course of study. But how I would integrate those fields I had not a clue (laughs), I just knew I did not want to give up my attachment to each.

There were a series of moments where things started to narrow in ways that would integrate and synthesize. I realized that my principle interest was historical from Marion Ross [and during] Tom Hubka’s studio where he was studying Polish wood buildings. First, he was studying something that had to do with my Jewish heritage; second, with this aspect of the Holocaust—about how many [synagogues] had been destroyed—it was part of a story I knew and found quite haunting and part of my community history. So [I realized] you could connect your own identity and things you deeply cared about to the work you do and it could be historical. This was very striking to me, I hadn’t had that idea, I didn’t know that architecture encompassed that.

Then there was a course that Rosaria Hodgdon taught about the city, and I realized my interest was urban, deeply urban. She even said, Given your interest you might want to go into planning. The event that took the whole thing over the top was an honors seminar in the College of Arts and Sciences that a young historian, Bob Berdahl, was teaching. He had just come back from a sabbatical at Princeton and he was crazy-excited about the idea of social history, that you could do history not focused on elites but about ordinary people. By the end of it things started to gel—that I could do work on historical matters and apply these ideas to the social history of the built environment.

It was a slow process of discovery through novel, exciting experiences with faculty at a research university who were not only outstanding practitioners but who had a curiosity about new things and they conveyed their enthusiasm in the classroom. It’s the difference of going to a research university where the original pursuits of the faculty can really excite learning. … [The faculty at UO also] made me a more reflective teacher.

Q: What about vernacular architecture captured your attention?

A: In a strange way it was my political philosophy, which was highly democratic, empowerment focused. It was the time, too. It was clear to me that the idea of studying only buildings designed by architects left out 99 percent of the buildings that people use and live among. I’ve always had an inclination to study what’s not been covered—[no one] needs another Frank Lloyd Wright scholar, but there are a lot of topics that have not been pursued. But also I could identify with the phenomenon that buildings don’t always exist in the moment they’re designed, and not all their creators are architects. If you move from [how buildings] over their lifetimes have been used and what they mean to people, then you come closer to the things I’m passionate about. Then it was just a small leap to, Would there be a reason to preserve them? And on what basis? And how would you document them if they’re not in a set of files of drawings? So it opened up a whole new set of questions for me.

Q: How did that translate into your focus on researching the Japanese-American built environment?

A: I had a mentor [at UCLA], Dolores Hayden, who was working on what at the time was a path-breaking project, The Power of Place, that was rewriting the history of Los Angeles through buildings that reflect the multicultural heritage of the city. It was a different map of the city [integrating] urban design, preservation, public art, and public historical interpretation. That was where all of my interests, my career, solidified. I took a slice of it—women’s history sites—for my dissertation but also worked for Hayden on her Power of Place project and was assigned properties associated with Japanese-American heritage in the city.

So I was primed when I got my first academic job, at University of Washington. The state historic preservation office had a contract to survey the scope of Asian-American resources in every one of Washington’s counties. I only had part of the skills—the preservation skills—so I had to figure out the tools to do a survey that would cut across multiple ethnic groups because this included Chinese-Americans, Japanese-Americans, Filipinos, and so on. I assembled a team and we worked to figure out what you could predict, based on the scholarship, would be the most important kinds of resources that would be out there. It was a very comprehensive study … documenting the properties and predicting what [else] should be out there, and those predictions led to finding resources we weren’t aware of.

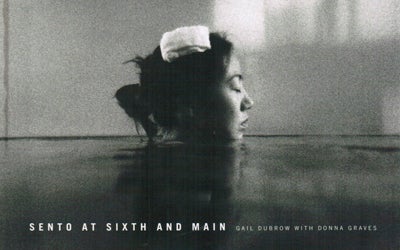

A great example of that is Japanese-American bathhouses … at the Panama Hotel and on rural farmsteads where Japanese-American families were tenants. We could predict [the existence of the bathhouses] from what we knew about the literature but we’d never gone out and actually documented any. That led to a National Historic Landmark designation for the Panama Hotel. With the Japanese-American community there was a resonance in terms of their willingness to work with me, getting engaged with the community, having a series of relationships that got me deeper and deeper involved. That grew to a set of relationships across the West Coast in Japan towns and Japanese communities. It ended up being a detour I never expected to take, but it’s a very compelling subject.

Above: Sento at Sixth and Main: Preserving Landmarks of Japanese American Heritage, written by Dubrow with Donna Graves (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2004).

In the 1980s, the Japanese-American community won a public apology and redress payments under the Reagan Administration. What people don’t know is that with those $20,000 payments to individuals and the apology came a multimillion-dollar fund that Congress set aside—called the Civil Liberties Public Education Fund. A lot of the energy of the community, which had been focused on redress, [then] focused on preserving the internment camps like Manzanar and Minidoka. I came to the conclusion that you couldn’t understand the depth of dislocation, disruption, and destruction of The Internment if you didn’t look at the communities Japanese-Americans had built before the war. How [else] would you know what was lost, what was their status, who were they, what had they built for themselves, and then what happened to what they built? That led me to write Sento at Sixth and Main.

Q: Will the two inquiries you are currently working on—Preserving Cultural Diversity in America and Japonisme Revisited—become books?

A: Yes. Preserving Cultural Diversity has been long in the works and it’s based on these layers of works I’ve done on preserving women’s history, ethnic history, and now gay and lesbian history, so it addresses the full spectrum of cultural diversity. Its intention is to move beyond the focus on these particular groups and their identity to help them see what they have in common as allies that might change the preservation movement. Kind of a new majority.

The Japanism project built on what I’ve learned about Japanese-American history, but [it investigates] those elites, particularly white Americans, who became infatuated with all things Japanese at the same time America was trying to drive out people of Japanese descent and get them to not practice their traditions, under the rubric of Americanism and assimilation and patriotism. It asks the question, What goes on in culture when the majority adopt and appropriate ethnic culture—Japanese gardens, Japanese architectural style and buildings, ceramics, infusion of Japanese aesthetics into impressionism and other art movements—while immigrants are being driven out and told they should not behave like Japanese.

There’s a side point that comes from the first question you asked about interdisciplinarity that I wanted to elaborate on: My many experiences trying to integrate fields across disciplines and then as a faculty member who had appointments in multiple departments, and got tenure in multiple departments—it’s not the easiest thing—all of those led me to ask what are the barriers in universities to teaching and research or the construction of academic buildings or giving multiple credit on grants or fundraising, that involve multiple colleges. It led me to ask questions about what are the institutional barriers and try to figure out what are the best practices for making interdisciplinarity that faculty and students just do naturally. How can we bring our institutions up to date and move them out of the traditional modes of funding that goes to colleges, which goes to a department and all the incentives are structured disciplinarily.

I’ve done a lot of work over my administrative career to try to facilitate interdisciplinarity and it culminated in building a ten-university consortium, the Consortium on Fostering Interdisciplinary Inquiry. It came out of my personal experience [that led to] trying to develop scholarship of leadership around interdisciplinarity. The thing that was unique about it was that a lot of past meetings and gatherings just brought faculty together, or faculty and students, to talk about it. But no one tried to bring the administrators together, probably because it’s difficult. But I convinced ten universities to contribute to and participate in self-studies of interdisciplinarity at their institutions and to learn together what the best practices and barriers might be. I had them form teams consisting of people like the chief financial officer, the provost, each level of administrator, VP for research, that kind of thing, and I had them meet in their teams but also with their peer at the other universities so that all the financial officers met, all the capital construction people met, and so on, and they figured out what the barriers were at their institutions. So the recommendations are theirs, not mine. [The schools are University of Minnesota, Brown University, Duke University, University of California, Berkeley, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, University of Michigan, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, University of Pennsylvania, University of Washington, University of Wisconsin-Madison.]

Q: How did you make that happen?

A: I was vice provost and dean of the Graduate School [at the University of Minnesota], so I had a platform to speak from. I got a major investment from my president and provost in doing this. Our aspiration was to be among the leaders of innovators, and the other institutions all had built reputations around interdisciplinarity. … I have this philosophy: You can both cooperate and compete your way to the top. This was a model of both. By cooperation, we were going to figure out what the patterns were that we couldn’t find out from our own institutional alone. It was the right moment in time where institutions were trying to establish their national reputations but not all of us could establish them on the same metrics, and being a leader in interdisciplinarity had some currency. It was the culmination of a lot of years of thinking and working in smaller scales, but we did it, we got it done, we got a report out of it. (Dubrow later gave a presentation about the project to the UO Board of Deans.)

Let’s relate it back to A&AA: The thing I most admire about A&AA—not only the phenomenal education I got—but, as a school, all the parts are there. A lot of us aspire to integrate—say, for example, at Minnesota we want to integrate planning and policy with design and urban design—but we’re located in different schools and colleges and although we can build the bridges among and between us, it’s not easy. But at A&AA you’re all here under one umbrella. So if any school has the potential to integrate in, say, the next decade, in ways that build synergies across fields, this is it.

To me it seems like it’s one of the agendas we’re all looking at in colleges of design—taking the time to learn about what are the structural and institutional barriers to crossing disciplines and developing fixes and workarounds that, for example, provide the financial incentives that make it easy for faculty to cross over and for students to sample and borrow from all, and even to integrate certain fields without losing identities. And it’s not just college-wide or school-wide but integration with the rest of the university.

Some of those large provost- or president-driven initiatives where A&AA has fared so well in in the past few years [such as] funding around [the] Sustainable Cities [Initiative]—they mostly require partnerships with other colleges, right? So figuring out how to work together on those kind of initiatives in ways that don’t just fuel faculty research but so inquiry becomes the heart of student learning—to me that is next-decade agenda. I have a lot of hope for what you’re going to be able to do here. Faculty have already been doing it [interdisciplinarity]. Students have already been doing it. The number one thing is the university organizing itself to facilitate it.

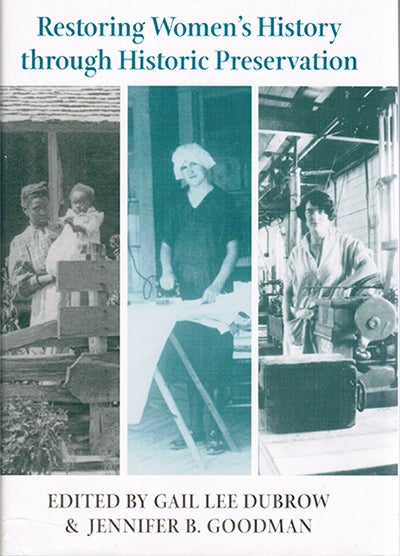

Q: Since publication of Restoring Women’s History in 2003, do you feel that the effort to elevate the visibility of women’s historic sites has made the degree of headway you hoped for when the book came out?

Above: Restoring Women’s History Through Historic Preservation, coedited by Dubrow with Jennifer Goodman (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003), won the Antoinette Forrester Downing Award from the Society of Architectural Historians for the Best Book in Historic Preservation.

A: There continues to be movement forward. At the time I wrote it, it was at, say, Stage 2 of the effort. Stage 1 there were about five people who cared but it hadn’t gained traction in any kind of mainstream. Today, if you go to the National Trust’s website they have pages devoted to women’s history, and initiatives for ethnic history, and they are champions of LGBT history, and they have subgroups organized and representatives among their advisers—they’re on board. But many local preservation efforts are still organized around local surveys of places with no guarantee they’ll be sensitive to ethnic history, or women’s history, or LGBT history, or any particular group … sensitivity to things that are not visible from a windshield survey. You’d have to do underlying research and have a sensitivity and awareness.

The time has come to reexamine the degree to which much of the standard work done in preservation has fully integrated these ideas. ... It’s about preservation practice and the bread and butter of survey work that’s done—context documents, survey work about whether we get experts in these fields to read and review their work, to be on the teams, whether we have a kind of insistence that inclusiveness is going to be a part of all the work we do. And that’s not unusual as a next-stage agenda; it’s the integrative nature of it in any work we do. There’s new work coming out on LGBT history and its interpretation, work coming out of Hispanic preservation initiatives that’s going to enrich all of us, but we’ve done the basic work on women at this point. At this point we need work that deals not with just white women but women of color and the lesbian part of LGBT, not just gay men sites. It’s the cross-fertilization across all these areas.

In terms of recognition from this medal from A&AA, it’s less about me [and] more about how the field has changed: Finally, what was at the margins has come to be part of the mainstream. It wasn’t that fun at the beginning—to be ignored, then ridiculed, then fought viciously. The irony for me is … I get recognition for doing work, over a lot of years, that was unpopular, unfavorable, and definitely against the grain. And that’s what you hope for, to make a difference, to move the needle.

Q: You obviously figured out a long time ago that research can be enlightening and fun. How do you convey to students how riveting and life-changing discovery can be ... that’s it’s not just a hard trudge through library stacks?

A: I have an advantage, which is that to teach students research I don’t only have them read research, but they get out into the field to discover things. I’m thinking about one project we’re doing at a place called Neely Mansion, which is known for the first white pioneer in the valley settling there. I asked my students to look at the layers of history there and then literally we went out in the field to do the research. What we first learned was there were Japanese-American families who lived there almost for the entire history of the property; the Neely family was only there for a few years. We predicted that if there were Japanese families there, there would be a Japanese style bathhouse—but there wasn’t when we looked around. But in the course of walking around the property with a Filipino family who occupied it after Japanese-Americans were interned, they said there used to be a shed with a Japanese bathhouse. And one of them remembered pulling it away with a tractor. So we started marching around the property and over to where it had been subdivided and there was the bathhouse, sitting on the adjacent property.

As a result of that ‘research’—which felt like play—the Neely Mansion Association moved it back next to the house and uses it to interpret Japanese-American presence and is now in the process of restoring it. So does that [research] sound dull? It’s some of the most memorable experiences my students have because it lacks the kind of remoteness and dullness of research without purpose exactly or an audience. It has a real impact in the world. It has a lot of modes of discovery: There’s the learning through elders and what their memories and experiences are; it’s the learning through the physical surveying and the nature of materials—buildings, form; it’s archival research to answer questions, and they really do answer the questions you’re looking for like how long were the [family] there, what did it look like in those days—research with a real purpose. And anyone who goes there as tourists now will learn about this history that was just an idea that other ethnic groups occupied the property. So we’ve done a public education function.

It’s the trail of a mystery, then you get excited about each success you have in finding the piece of the puzzle. Not all students take to research and not all would like careers like that, but all leave with a sense of it’s a much more dynamic, exciting field than it might look in other disciplines. Now they call it active learning. We just called it an architectural education.

Interview by Marti Gerdes

This story was published as part of the 100 Stories collection, compiled to celebrate our 2014 centennial and recognize the achievements and contributions of our alumni worldwide. View the entire 100 Stories archive on the College of Design website.