master of historic preservation, ‘07

Alumna’s passion for preservation started at age 14

Sueann Brown jokingly refers to an incident at age 14 as her “first arrest,” even though it remains her only arrest.

She and her older sister were walking home from middle school when they noticed bulldozers parked on her street in Takoma Park, Maryland, a suburb of Washington, D.C. A construction crew was about to tear down an old Victorian house to pave a parking lot for a nearby community college. Several neighbors had installed themselves in front of the bulldozers to impede the demolition, and plenty more joined them, including Brown and her sister.

“I really have always had a real passion for historic architecture and it seemed like such a shame for people to be tearing it down,” Brown says. “I didn’t want to see it go away.”

Above: Sueann Brown, MS ’07, at the backcountry Saint Andrews Cabin in Mount Rainier National Park. Photo by Saylor Moss.

Eventually, the protestors who obstructed the project, including Brown and her sister, were arrested and booked. The house was subsequently torn down.

Their mother was not amused.

“She raised us to have a level of social consciousness and took us places where we could see and appreciate things like historic structures,” Brown says. “I still like to think that she was secretly proud of us, but she did not express it that way at all.”

Brown recognizes now that her youthful defiance was probably not the most effective way to save the old home.

“There’s obviously a certain romance in civil disobedience,” Brown says, “[but] it wasn’t an effective means of preserving historical structures. I’ve gotten to learn more effective means of historic preservation and working within the system to preserve what we can.”

Brown, who earned her master’s degree in historic preservation from UO in 2007, works today as historic architect and lead for the National Park Service Pacific Northwest Region’s Historic Structures Program in Seattle, Washington. She provides technical assistance on preservation projects for more than 5,000 historic buildings and structures in sixty-two national parks in a region that includes California, Hawai’i, Idaho, Nevada, Oregon, Washington, and U.S. territories in the South Pacific.

“We are trying to provide advice to the parks and help maintain historic character to the greatest extent that we can, while recognizing that some amount of change is inevitable,” Brown says.

Her role ranges from routine treatment and maintenance recommendations on historic structures (such as specifying and sourcing roofing materials) to challenges such as adapting historic structures to meet modern seismic code requirements, compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act, or ensuring that new construction fits appropriately in a historic district.

While still putting herself through school at Virginia Tech, Brown bought her first house—a modest-sized home in Blacksburg, Virginia—when she was just 21.

“It was a total dump,” she says of the home, which came with a $12,500 price tag.

The house became Brown’s first hands-on preservation endeavor; she fixed it up, lived there, and eventually sold it.

She earned a bachelor’s of architecture degree from Virginia Tech in 1982, when jobs in architecture firms were scarce nationwide due to the economic downturn at that time.

“Everyone was laying off their cousin and their brother,” she says. She found a job with the Roanoke Housing Redevelopment Authority in Roanoke, Virginia. With the City of Roanoke offering loans to low-income residents who couldn’t afford to maintain their homes, Brown conducted inspections to determine what repairs or improvements were needed. She prepared plans and specifications for the work, and oversaw the contractors who performed it.

“I really liked helping the people we were working with, many of whom were elderly folks on fixed incomes,” she says. “It was great being able to save old buildings and old people at the same time.”

She purchased her first rental properties in Roanoke, a duplex and triplex on adjoining lots built in the 1910s. She wasn’t planning on buying the properties but drove by, saw the for-sale signs out front, and thought, “Someone needs to save these houses.” The homes were abused; one had an enclosed front porch with tacky aluminum windows and fake brick siding, and was in need of a new roof. They both needed new paint.

“You could tell driving by that it needed a lot of work,” she says. “You could tell underneath all that stuff that it was a beautiful old house.”

The fake brick siding and aluminum windows were stripped off and the historic details recreated. Of the thirteen houses Brown has owned over the years, eleven were built before 1927.

“All of them needed work and each has given me a new learning opportunity, depending on the type of work it needed,” she says. “I really enjoy hands-on preservation work and I think it gives me a little more credibility when I’ve done the work that I am asking others to do.”

Brown eventually fell in love with Portland and the Oregon Coast. Her first job on the West Coast was a very similar line of work as she had in Virginia. For ten years, she managed various programs for Washington County, in the Portland metropolitan area, that provided home repairs for low-income homeowners throughout the county.

But the county housing stock was predominantly newer suburban neighborhoods, which she found much less interesting than the older homes she had worked on in Virginia. That helped her look into pursuing a master’s degree in historic preservation.

She started by attending two of the UO’s Pacific Northwest Preservation Field School’s week-long summer sessions, plus, in 2002, the month-long field school in Europe, held at that time in Oira, Italy.

“That month in Oira with [then-Field School Director Don] Peting and [then-Professor of landscape architecture Robert] Melnick changed my life,” Brown says. “I learned so much from both of them. Obviously they taught me a lot about historic structures and cultural landscapes, but for me the most important lesson that summer was the example they both provided of how we should live our lives—spending time doing things we are passionate about. It was the last inspiration I needed to apply for grad school.”

So she enrolled in the UO’s Historic Preservation Program as a master’s degree candidate, and was hired as Peting’s graduate assistant.

“Every time I’m in Don’s presence, I learn something,” she says. “He’s a really great resource for the university. I can’t say enough about what he’s done for my career.”

During a field school visit to Honeyman State Park—south of Florence on the Oregon Coast—Brown began work on her thesis, which examined the design and construction of historic structures built by the Civilian Conservation Corps in state parks. Since the National Park Service was responsible for overseeing the CCC’s design work in state parks, Brown intensively studied Honeyman State Park and Yosemite National Park to develop her thesis.

She has returned to the field school as a guest lecturer nearly every year since graduation, often lecturing on topics related to her thesis.

“It’s a pleasure to have her at the Field School because she’s so knowledgeable and thoughtful and does wonderful presentations,” Peting says. “I’ve learned a great deal about the CCC from her, and always look forward to learning more.”

Brown learned of her dream job from a guest lecturer at the field school. Historical architect Hank Florence delivered a talk that explained his job for the National Park Service. This career path introduced Brown to a nexus of her passions: historic preservation and the outdoors. Today, she sits literally a few desks away from Florence in the same office in downtown Seattle.

“It sounded to me like he had the coolest job in the world, but it didn’t sound like there were many historical architects working for the NPS,” she says. “I didn’t set it up as a goal; I got lucky.”

She was still working on her thesis when she was hired at Yosemite—and several months later adopted a cat. After some trouble deciding on a Yosemite-related name, Brown eventually landed on “Wosky,” in honor of early NPS architect John Wosky, who designed NPS buildings in Yosemite for decades and played a role in the development of the rustic architecture that became the signature Park Service style. That style included a specific color of exterior paint, referred to as “Wosky Brown,” on every building.

Thus, she had the perfect first and last name for her cat: Wosky Brown. A resilient feline, Wosky has moved with Brown from her post at Yosemite to Mount Rainier National Park, and finally to her current position in Seattle.

Above: Brown takes a break from backpacking a section of the Wonderland Trail in Mount Rainier National Park. Brown was the park’s historical architect for four years; prior to that she worked at Yosemite National Park as historical architect. Photo by Marti Gerdes.

Brown still maintains a strong connection with the UO. In 2009, for example, she asked if UO preservation students in a condition assessment class could travel to Yosemite to evaluate seventy-two structures in an area damaged by a rockslide when car-sized boulders rolled through a campground. The students were asked to help determine which structures could be saved, moved, or demolished.

More recently, she advocated that Mount Rainier National Park host a UO Pacific Northwest Field School summer session, which the park agreed to do in 2016, the 100th anniversary of the National Park Service.

“It's exciting because it's great for field school to be in a national park during the centennial for the NPS and it gave me a chance to do something I hadn't done yet for Field School: I've been a student and I have been a guest lecturer. Finally I got to be the host.”

The students worked on a fire lookout in the backcountry, as well as cabins for seasonal workers built by the CCC in the 1930s in the Mount Rainier National Historic Landmark District. Students replaced rotted timber framing, repaired wood windows, and repaired masonry features.

Brown’s encouragement of her Park Service colleagues to bring UO students to the park is just another example of her enthusiasm to spread the word about parks as a career for historic preservation students, and reminding park administration that students are eager to provide a hands-on preservation workforce—a win-win for both parks and students.

“Sueann is passionate about preservation,” Peting says. “She has a remarkable ability to clarify to a lot of administrative people she has to work with the importance of that preservation. … It’s a first-rate position and she’s so capable and calm about making decisions that she’s perfect for it.”

Upon hearing about the 14-year-old Brown’s rebellious activism, Peting says it’s a familiar story for many historic preservation students.

“A lot of [students] are responsible for making their communities understand the importance of its historical fabric,” he says. “It’s another measure of how deeply caring she is about the work she does and the places with which she is involved.”

Through her NPS role, Brown has great influence on preserving timeworn and historically significant structures, a role arguably more effective than blocking bulldozers.

“I have learned to find out the ways and means of preserving places I care about in a much more effective way than I did when I was 14,” she says.

“Now I have the right tools to do it. I know preservation laws and principles and what I learned in school that I’m now able to implement in my daily work. It feels really good,” she says—but “deep down, I’m still that 14-year-old.”

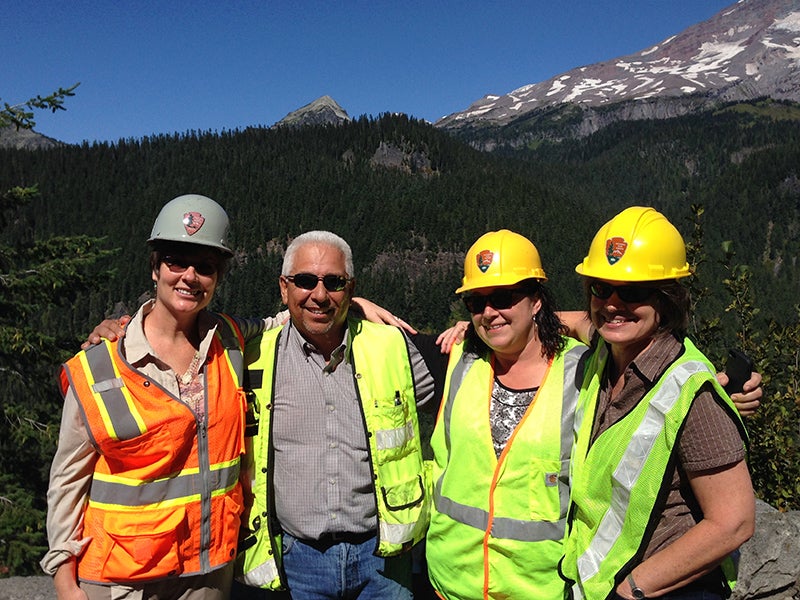

Above from left: NPS Park Cultural Landscapes Program head Susan Dolan (BLA ’94, MLA ’96), Federal Highway consultant Pete Gonzales, NPS historical landscape architect Saylor Moss, (BLA ’06), and Brown during a work break at Mount Rainier National Park. Photo courtesy Sueann Brown.

This story was published as part of the 100 Stories collection, compiled to celebrate our 2014 centennial and recognize the achievements and contributions of our alumni worldwide. View the entire 100 Stories archive on the College of Design website.