Trees that punctuate a city sidewalk may appear to be passive or almost inanimate, but throughout history they have been a source of conflict. Planting trees in the cityscape even became a means by which women publicly asserted themselves as activists, reformers, and design professionals throughout the twentieth century.

Sonja Dümpelmann, from Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design, will discuss the politics of street trees when she presents the 21st Annual Mary Kim McKeown Memorial Lecture in Landscape Architecture at 6 p.m. Wednesday, January 20, in Lawrence Hall Room 177 (1190 Franklin Boulevard). It is free and open to the public.

Sonja Dümpelmann, from Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design, will discuss the politics of street trees when she presents the 21st Annual Mary Kim McKeown Memorial Lecture in Landscape Architecture at 6 p.m. Wednesday, January 20, in Lawrence Hall Room 177 (1190 Franklin Boulevard). It is free and open to the public.

The presentation by Dümpelmann, who teaches landscape architecture at Harvard, is entitled “Street Tree Stories: On the Politics of Nature in the City.” The lecture will focus on the role of trees in New York City and show how some of the biggest urban conflicts have revolved around them.

While trees are amenities to some, they are nuisances to others. Trees also became a source of female empowerment, Dümpelmann argues.

“Tree planting has been used by women to stake out and mark their own territory in the city,” says Dümpelmann, president of the Society of Architectural Historians Landscape Chapter. “Tree planting became a means of female emancipation and a means for women to occupy public urban space.”

In June 2015, Dümpelmann published an article, “Designing the ‘shapely city’: women, trees, and the city,” in the Journal of Landscape Architecture on this subject.

Dümpelmann previously studied the politics of landscapes, the role of landscape architects in Italian fascist politics, and how different countries have exploited trees for purposes of political diplomacy.

The historical role of street trees is vast and various, encompassing both those who advocate for and those who resent their existence. Some New York City business owners on Fifth Avenue disparaged trees because they blocked the view into their storefront windows.

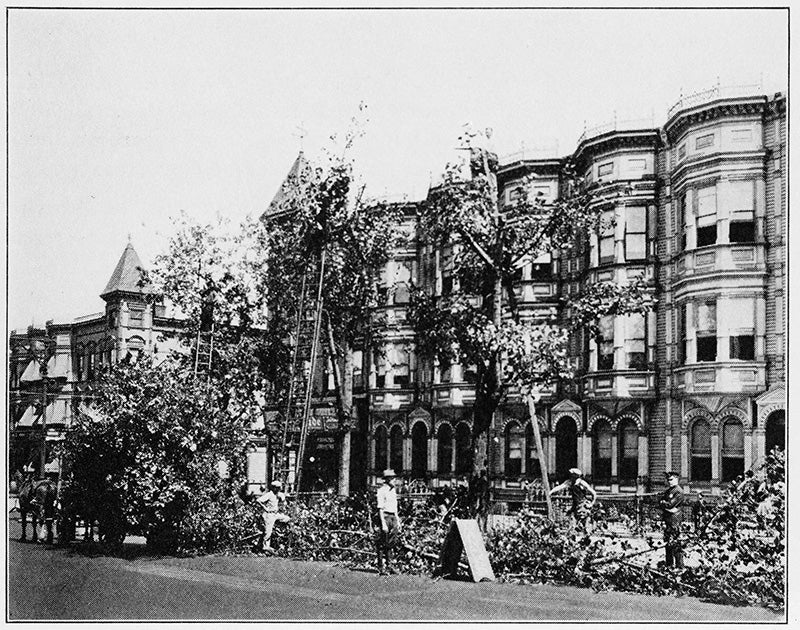

Above: The historical role of street trees encompasses both those who advocate for and those who resent their existence; some of the biggest urban conflicts have revolved around them, with trees being amenities to some but nuisances to others. Some New York City business owners on Fifth Avenue disparaged trees because they blocked the view into their storefront windows. Image courtesy Sonja Dümpelmann.

In Rome during the 1920s and ’30s, trees were used for political leverage. Architects and horticulturalists working for the fascist Italian government favored the “Italian pine tree” as pines were considered the “most Italian” of all trees, says Dümpelmann. All elm trees and other street trees in Rome were torn out and replaced with pines to turn the city into the capital of a new fascist empire.

“People might walk or cycle by street trees without thinking of these landscape elements having a context within a social and cultural history,” says UO landscape architecture Assistant Professor Mark Eischeid. “Decisions around street trees come from people. And people have biases and objectives and goals, so these trees are potentially lenses through which we can understand our own culture.”

Dümpelmann is working on a book about the close relationship between American forestry and German scientific forestry in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The book deals with the history of urban forestry and street tree planting in these countries.

Eischeid invited Dümpelmann for the lecture as well as for a guest critique in his studio, LARCH 539. Graduate students in the studio are developing a landscape master plan for the airport in Redmond, Oregon, and will present work and site analysis to Dümpelmann and other reviewers. The studio is a component of the Sustainable Cities Year Program (SCYP) yearlong partnership with Redmond.

In 2014, Dümpelmann wrote a book and co-curated an exhibition on airport landscapes at Harvard University. The book, which covers the history of airport landscapes and looks at how aviation and the aerial view have influenced designers and planners, is integral for Eischeid’s SCYP studio.

“I thought, what a great opportunity to bring somebody who’s an expert on the topic to Eugene for the benefit of our students,” says Eischeid. “It’s important for this studio and design practice in general that students are aware of the history of that particular site and type of project. I’m being intentional about making sure that an understanding of history is a part of the design process.”

The Mary Kim McKeown Memorial Lecture Series is made possible by contributions from friends, classmates, and family members in the memory of Kim McKeown, BLA ’82, to the University of Oregon Foundation.