Sally Donovan literally lives and breathes historic preservation, living in a 1913 house and using its “updated” 1931 refrigerator and electric stove every day for the past twenty years. And not long ago she finished, with her two partners and husband, first moving then rehabilitating an 1889 house destined for demolition, handling tasks from removing shingles to replastering and painting, along with the reams of paperwork required to buy the house (for $1) and arrange for its move (a lot more than $1).

A longtime Oregon-based cultural resource specialist and photographer, Donovan will be formally honored May 11 with the 2016 George McMath Historic Preservation Award, presented each year to an individual whose contributions have raised awareness and advocacy for historic preservation in Oregon. Tickets for the award luncheon at the UO in Portland will go on sale after April 1 at hp.uoregon.edu/mcmath. Tickets cost $50.

Above: Sally Donovan

Donovan has led Donovan and Associates, a historic preservation firm in Hood River, Oregon, since a year after her graduation from the UO’s preservation program in 1987. Her list of National Register nominations, building surveys, preservation plans for counties and cities, large-format photography of historic properties, master plans for historic districts, environmental impact statements, and more runs well into the hundreds. Her firm, a Certified Woman Owned Business, specializes in the preservation and treatment of historic cemeteries.

“Sally’s exemplary body of work over twenty-eight years very materially helped to set the high standard for cultural resource documentation in Oregon,” said Elisabeth Walton Potter, BA ’60, formerly the National Register coordinator for Oregon’s State Historic Preservation Office. “What stands out in Sally’s record is unremitting quality across a broad range of resource types, whether publically or privately owned, and all types of documents.”

Donovan’s work inspired the Eugene Masonic Cemetery Association to carry out monument and burial plot rehabilitation as well as restoration of Hope Abbey Mausoleum by dozens of volunteers over the past twenty years, said Ken Guzowski, retired senior planner for historic preservation at the City of Eugene.

“Sally has in her modest way advanced our knowledge of local history, the people who created these [significant] resources, and promoted the importance of preserving all types of cultural resources representative of Oregon and our region,” he said.

Guzowski lauded Donovan for helping to train new generations of preservation practitioners. Many graduates of the UO’s Historic Preservation Program, he said, “have informed me that because of being hired by Sally fresh out of graduate school, they were exposed to the highest level of professionalism with historic preservation practices.”

Donovan earned a bachelor of fine arts degree with an emphasis on graphic arts, photography, and painting from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. After college she worked as a cartographer, graphic artist, photographer, and technical illustrator for agencies ranging from the Alaska Department of Fish and Game to the University of Nebraska’s Division of Archaeology Research and the University of Oregon’s Department of Physics.

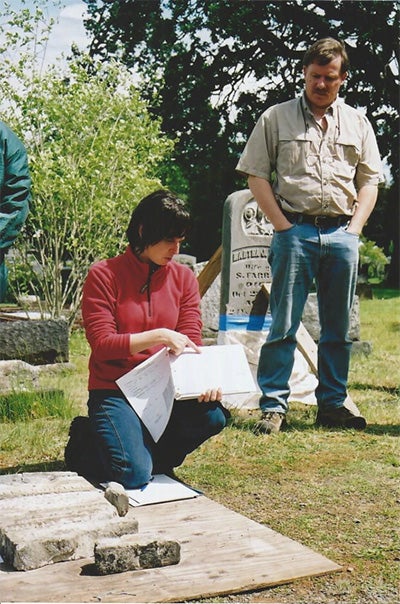

Above: Donovan teaches a class at Pioneer Cemetery in Salem, Oregon. Photo by Elisabeth Walton Potter.

Her interest in cemetery preservation started as a kid when her mother took her to see relatives’ graves and other historic cemeteries in Nebraska.

“I was fascinated by the headstone imagery and stories told by the epitaphs,” she said. Later, during college, “I lived next to a cemetery and started photographing headstones and found it a very peaceful place to walk and enjoy nature.”

After graduating with her fine arts degree, her work as a technical illustrator and cartographer included field work with archeologists to document and map prehistoric and historic sites in western Nebraska.

“That is when I began to look at careers in historic preservation,” she said. “Amazing homesteads were tucked away in the river valleys along the Niobrara River. We photographed the sites, drew site plans and floor plans, and it was a fun way to spend the summers, outdoors documenting the history of the area.”

She wasn’t sure where a preservation career would take her, but she welcomed work that was “not behind a drafting desk,” she said, so enrolled in the UO’s Historic Preservation Program. “I’m happiest being in the field and that is why cemetery work has become more appealing. It’s hands-on and always presenting a problem to be solved.”

Her focus on cemetery work came early in her consulting career, when one of her first contracts was to prepare a preservation master plan for the Jacksonville Cemetery in Southern Oregon. “It was a great opportunity to study the various components of historic cemeteries from the road circulation patterns, signage, fencing, landscape features, block enclosures, management, and cemetery objects,” she said.

Other cemetery projects came her way as a result, sparked in part by formation of what is now the Oregon’s Commission on Historic Cemeteries, a division of the State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO), who contracted with Donovan to conduct training workshops on how to care for historic cemeteries.

Donovan and her husband, Bruce Howard, have now been working together for about fifteen years repairing gravestones and conducting workshops at several sites throughout Oregon. She and Howard teach appropriate techniques for re-setting tilted, leaning, and fallen markers, and for documenting dislocated grave markers and marker fragments.

Her work in cemetery preservation was recognized in 2016 by Oregon Heritage, who named Donovan a recipient of a 2016 Oregon Heritage Excellence Award for her dedication and outstanding work on behalf of Oregon’s heritage resources, including her leadership in working with historic cemeteries. “The recipients represent the diversity of efforts to preserve Oregon’s heritage,” said Kyle Jansson, coordinator for the Oregon Heritage Commission. “They also serve as models for others for how to make the most out of available resources.”

Above: Carefully placed clamps stabilize broken pieces of a gravestone while specialized cement dries. Photo by Sally Donovan.

Her business footprint continues to evolve. “My brother and my brother-in-law have been helping with the work” recently, she said. “A family business! And my niece, Adrienne Donovan Boyd is a graduate of the U of O preservation program but I have not gotten her out in the cemetery yet, although we’ve worked together on other projects.”

The McMath Award is hardly Donovan’s first public recognition of her superlative work and remarkable productivity. In 2006 the Benton County Historic Resource Commission and Corvallis Historic Preservation Advisory Board presented Donovan with their Annual Preservation Award for her National Register of Historic Places nomination and preservation master plan for Crystal Lake Cemetery in Corvallis. In 1996, the Oregon State Historic Preservation Office bestowed its CLG (Certified Local Government) Award on her for her efforts on behalf of the Eugene Masonic Cemetery.

Donovan served as an adjunct instructor in the UO preservation program over a period of ten years. In 1995, her students immersed themselves in assessment and conservation techniques through hands-on field work she directed in the Eugene Masonic Cemetery.

“The work has included reconstruction of delicate marble tablets that were shattered by vandals. As well, the team has righted monuments, recreated missing parts, and trained and worked with volunteers,” Guzowski said. “Her knowledge includes a keen awareness of 19th-century burial customs as well as understanding the monument types and their creators. Sally is highly effective because of her down-to-earth style and willingness to explain complex methodology and preservation practices to students and volunteers.”

Kuri Gill, coordinator for Oregon’s Historic Cemeteries Program, added that “Sally has truly changed the story for historic cemeteries in Oregon. Her plans were a model for our workbook offered to people to help develop their own plans. Her love for cemeteries and her compassion for people who care for them is truly remarkable. She always leaves people feeling confident in using better [restoration] methods.”

Above: Cape Arago, Oregon, 2008. For the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) and Historic American Engineering Record (HAER), by Sally Donovan.

Donovan’s other contribution to preservation has been the extraordinary quality of her photography.

“Her photographs—particularly the large-format black and white photographs identified with HABS and HAER documentation—are suitably objective but go beyond to an artistic quality that is the result of her well-practiced work in the darkroom,” Potter said. HABS (Historic American Buildings Survey) and HAER (Historic American Engineering Record) are the backbone of the National Park Service’s Heritage Documentation Programs.

HABS/HAER records are housed at the Library of Congress. Googling Donovan’s name in the online collection results in 261 photographs by Donovan taken throughout the American West during her career, an astonishing contribution by just one photographer.

Donovan has also incorporated historic preservation as a method of urban revitalization that renews diverse, older neighborhoods, addressing appropriate infill ideas while advocating for the preservation of primary structures. She wrote a comprehensive brochure for the City of Eugene that explains, in layperson’s terms, the financial incentives to property owners interested in historic preservation as a wise investment.

But it’s the outdoor projects that she mentions most upon reflecting on her career highlights. One of those was the Cape Arago Lighthouse on the Oregon Coast. “Bruce and I spent three days on the rock island documenting the lighthouse and bridge photographically and architecturally for a HABS/HAER project,” she said. “The site was spectacular. To be able to feel a little bit what the lighthouse keepers’ lives were like was a rare opportunity.”

Above: Interior of south wing, facing west, Camp Tulelake Barracks, Tulelake, California, 1997. For the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) and Historic American Engineering (HAER), by Sally Donovan.

Another “amazing” site to work at was Bodie Historic Cemetery in Bodie, California. “The location was one of the most desolate we have worked in and it was interesting to learn the philosophy about ‘arrested decay’ in managing the town as a National Historic Landmark,” she said. (In arrested decay, no attempt is made to improve a ruin but measures are taken to prevent it from further deterioration.) Donovan wrote the Cemetery Preservation Management Plan for the site and conducted a training workshop in partnership with the UO and the National Park Service.

“She’s been doing work on a host of differing projects across the country and has developed a terrific skill in doing cemetery preservation,” said Don Peting, UO Professor Emeritus of architecture and historic preservation, who joined Donovan for the Bodie workshop. “At Bodie she brought in specially trained dogs to help locate gravesites. We were there with both dogs and modern ground-penetrating radar and it was the dogs that accurately located the graves. Sally’s knowledge and innovative practice in her preservation work and research is just amazing.”

Above: Sally Donovan with her large-format camera at Cape Arago Lighthouse, Oregon.

Donovan credits her UO professors, the late Philip Dole and Mike Shellenbarger, for helping her understand “settlement patterns and how to look at a historic building” as well as their expertise in historic masonry. Other key influencers for her career were Potter “for her mentoring on how to prepare National Register Nominations during her time at SHPO, and for her pioneering work with historic cemeteries” and the late architect Alfred Staehli “for helping me learn building technology, paint analysis, and large format photography.”

Advice she’d give to graduating preservation students wanting to open their own consultancy? “Carve out a specialty niche. Learn how to budget for projects. Learn how to work with all sorts of people—part of preservation is about listening, consensus building, creative solutions, and compromise. Don’t expect to get all glamorous jobs—you learn from each job and build upon that experience.”

Reflecting on the breadth and depth of her achievements, Donovan said she “feel(s) so fortunate to have had the opportunity to visit and research so many interesting places as part of my work, most of which I would probably have never otherwise experienced in my life. A variety of people,” she added, “have taught me how to be better at what I do.”

Donovan continues to pay that forward. “Her professional and friendly demeanor has brought many to the fold of historic preservation from the personal mentoring of volunteers and classes taught at the University of Oregon, to advocacy and public policy applied at the local level,” said Professor Kingston Heath, director of UO’s Historic Preservation Program. “Much of the important work that takes place in our nation to safeguard and commemorate our shared heritage goes unacknowledged by the general public. We, therefore, need to be thankful to those like Sally Donovan who tirelessly and competently perform the work of heritage conservation.”

Above: Detail of freight door, windows, and cupola windows on the north side of the Bayside Cannery, Santa Clara County, California, 1997. For the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) and Historic American Engineering Record (HAER). By Sally Donovan.

Above: Detail view showing roof and vent, looking north, Cape Arago Lighthouse, Gregory Point, Charleston, Oregon, 2008. For HABS/HAER, by Sally Donovan.

Above: Contextual view of A and B buildings from entrance of new hospital, looking east, Barnes General Hospital, 2006. For HABS/HAER, by Sally Donovan.

Above: Donovan, with partners Kim Lakin (MA '82, art history; MS '87 historic preservation) and Kristen Jones, bought and moved the 1889 Fargher/Steers House in The Dalles, Oregon, then rehabilitated it in 2007-08.

Above: Detail view showing central tower core, tower stairs, pipe railing, and fixed window, looking southwest, Cape Arago Lighthouse, 2008. For HABS/HAER, by Sally Donovan.

Above: Clinic surgery, interior view of X-ray room, looking north, Barnes General Hospital, East Fourth Plain Boulevard and O Street, Vancouver, Washington, 2006. For HABS/HAER, by Sally Donovan.

Above: Donovan and Howard after touring Mosier Pioneer Cemetery, above the Columbia River, where they had completed gravemarker documentation and repairs. Photo Ken Guzowski.