In 1965, a young labor organizer catalyzed what soon became an international movement to unionize farm workers seeking better wages and improved working and living conditions. Over the next thirty years, he would organize thousands of workers and lead millions of consumers nationwide to boycott purchases of grapes, lettuce, and wine, eventually changing agricultural practices in America.

That thirty-something union leader soon became a household name: César Chávez, who formed what later became the United Farm Workers (UFW). Chávez, farm workers, and the UFW are now the focus of Professor Robert Melnick’s fall 2013 landscape architecture studio.

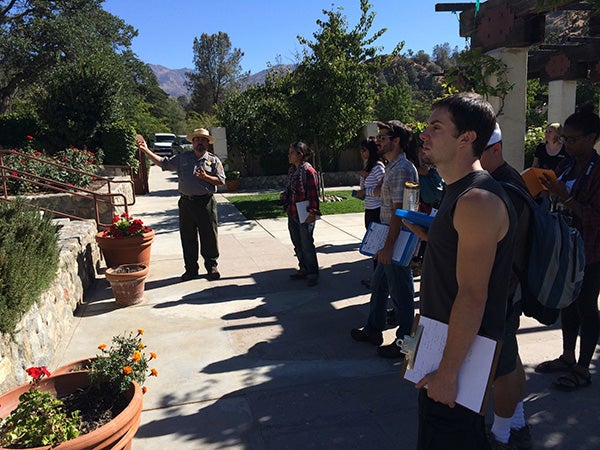

Above: Students in Professor Robert Melnick’s fall term studio pose during the field trip to the site, César Chávez National Monument in Keene, California.

Chávez spent his life working to improve the lives of farm workers through nonviolent efforts including hunger strikes, boycotts, and epic marches, one as long as 1,000 miles. By 1975, seventeen million Americans had joined the boycott and California enacted the first law in the United States that recognized farm workers' collective bargaining rights.

In 1971, the UFW moved its headquarters to Keene, California. Twenty years after Chávez’ death, in 1993, the headquarters site became the focus of Melnick’s studio: César Chávez National Monument (CECH). The National Park Service unit, one of the newest in the National Park System, acknowledges Chávez as the most important Latino leader in the United States during the twentieth century.

CECH is a unique partnership among the National Park Service, the César Chávez Foundation, and the National Chávez Center. A key reason Melnick made the monument the focus of his studio is because it’s in the earliest stages of planning and management.

“This is a rare opportunity to directly impact the future of a new unit of the National Park System, learn about a great American, and develop skills in cultural landscape work,” the course syllabus states. The monument is also known as Nuestra Senora Reina de La Paz (Our Lady Queen of Peace).

Melnick was “very excited” about the site after visiting it the first time “because it was a brand new national park—they’ve added nothing, which is perfect for us—and because I think Chávez was not well-enough appreciated nationally given all that he achieved.”

During zero week, the week before fall classes officially begin, all eleven students in the CECH studio flew to California for intensive site investigation plus meetings with representatives from NPS and the National Chávez Center (NCC). The NCC housed the group and provided about half their meals, while NPS footed the bill for airfare and other expenses.

The NPS has partnered with Melnick on many previous studios at sites including Mount Rainier National Park, Crater Lake National Park, Redwood National Park, and Olympic National Park. Melnick says the NPS invests personnel and financial resources in his studios because “they get enough cultural landscape inventory and design work [from the students] to use as a jumping off point for future work” in the parks. “Part of the Park Service mission is educational,” he adds, “so this serves that mission as well as serving the needs of the park.“

Above: Ruben Andrade, superintendent of César Chávez National Monument, talks to students in Professor Robert Melnick’s studio who visited the National Park Service site in September.

For CECH, his students will complete a draft cultural landscape inventory—a standard NPS cultural resources document—and develop design proposals for an interpretive trail. “Fifty years from now, just as we’re looking back at drawings from fifty years ago, someone else will be looking at this fifty years from now as a record of what existed in 2013,” Melnick notes.

The studio projects, which include documenting and recording the historic landscape of CECH’s 107 acres, give students hands-on experience in actual Park Service guidelines and practices, and a leg up should they pursue a career with NPS or other cultural resources-oriented firms or agencies.

A cultural landscape inventory identifies character-defining features such as land use, spatial organization, circulation, and more. It also includes a narrative of the site’s history, which in this case includes subsistence activities by native peoples, ranching, a quarry, a state tuberculosis hospital, and home and workplace of César Chávez and the farm worker movement. Based on their research, the students will then design an interpretive trail that integrates the national significance of the property in the larger environmental history of the earlier layers.

Asked whether his design students give him pushback when he assigns historical background reading and research, Melnick responds that “I don’t think I get resistance; I get questioning, but to me that’s what designers should do. The question is never ‘Why are we wasting time on this?’ It’s ‘Tell me more—I don’t quite get it.’ And the more we talk about it the more they get it.”

Above: The recently renovated 17,000-square-foot Villa La Paz Conference and Education Center at CHEC fulfills César Chávez’s dream of an educational center to train future generations of dedicated activists. The sprawling world-class conference and educational center was where Chávez held community gatherings and sessions with movement leaders and staff.

The students include both graduate and undergraduate students. All are landscape architecture majors except for one historic preservation graduate student.

“This class has already shifted my thinking from a building focus to something more landscape inclusive,” says Susie Trexler, the preservation student. “The landscape students and I notice different things. The studio has helped me look at cultural landscapes from a slightly different point of view. I hope that my contribution to the studio is to provide the same thing for the landscape students: a different point of view that they can think more about and apply to other cultural landscapes in the future.”

Landscape architecture graduate student Olivia Burry-Trice chose the studio as an alternative to the previous year’s “urban-based, relatively small scale” studios. “I am drawn to larger-scale planning and trail work and National Park Service work, so I felt like this was a great opportunity—and Robert is the perfect person to do that with. He’s really a great person to work with because he’s so motivated and so passionate about what he does.”

Graduate Teaching Fellow Noah Guadagni selected the studio because it “would be dealing with a national park that was just dedicated and needed a lot of ideas that could be implemented in the actual design and end result of the national monument. [And] Robert is retiring so this may be our last chance to get a studio with him.“

The studio’s final review, on December 6, will feature a who’s who of reviewers, including Paul Chávez, son of César Chávez, and Monica Parra, National Chávez Center events manager. Students will also have the acumen of Laurie Matthews, director of preservation planning and design at MIG in Portland; Vida Germano, cultural landscapes inventory coordinator for the NPS western region; and Susan Dolan, manager of Park Cultural Landscapes Program for the entire National Park Service, as reviewers.

Knowing the caliber of reviewers inevitably raises the bar for the students’ work. But judging from the students’ enthusiasm at midterm review, their self-imposed bar is already high.

“These students are all passionate about the site, passionate about César Chávez, passionate about the farm workers’ struggle and about how you communicate that,” Melnick says. “They are just on fire.”

In 1993, Chávez died in Arizona while defending the UFW against a multimillion dollar lawsuit brought against the union by a large vegetable grower. In 1994, President Bill Clinton posthumously presented the Medal of Freedom, America's highest civilian honor, to Chávez. In October 2012, President Barack Obama established César Chávez National Monument.