A team of UO landscape architects has won second place in an international competition to raise awareness of the true flood risk to people living in landscapes where the vulnerability may not be obvious.

Professor Kenneth Helphand, Associate Professor Liska Chan, and graduate students Shannon Arms, Emilie Froh, Carol Stafford, and Pieter Van Remoortere won second place in The “Watermarks” competition for their entry, “PDX Marks.”

When waters rise in cities, they leave their mark on infrastructure. Some cultures have recorded historical high water marks with plaques or lines on structures, a constant reminder that waters will rise again. However, “new developments continue to be built in the U.S on lands that will flood, but because they are ‘protected’ by levees designed to control the ‘100-year flood,’ under the rules of FEMA, these developments are not considered to be ‘in the floodplain,’ the competition webpage said. “Unfortunately, even if the levee works perfectly and protects against the 100-year flood, it is not designed to protect against the 200-year flood, or the 300-year flood, etc.”

The competition therefore sought innovative ways to accurately communicate the level of floods that will eventually occur, including inundation of unprotected floodplains by big floods, overtopping or failure of levees, failure of upstream dams, or coastal flooding.

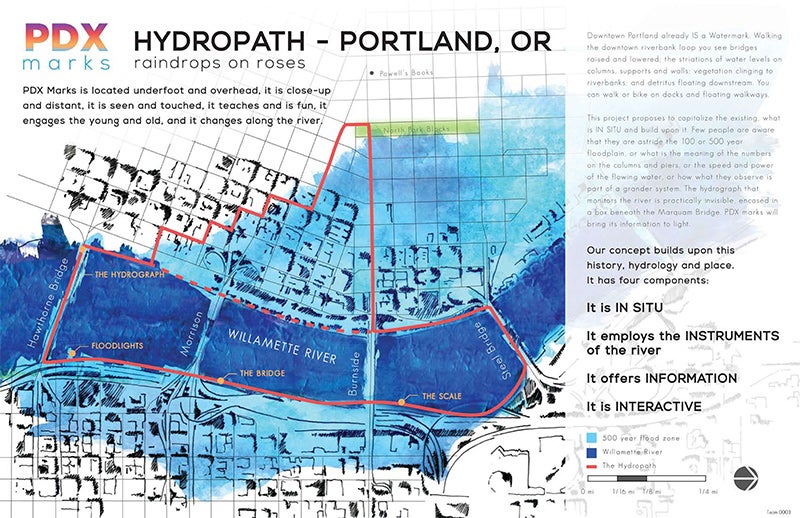

The UO entry capitalized on watermarks that already exist in downtown Portland, Oregon, turning ubiquitous bridge piers into colorful gauges showing future flood levels, and calling attention to rising waters through interactive features. The UO team won a $2,000 prize for PDX Marks.

“Downtown Portland already IS a watermark,” the UO project’s narrative begins. “Walking the downtown riverbank loop you see bridges raised and lowered; the striations of water levels on columns, supports and walls; vegetation clinging to riverbanks; and detritus floating downstream.

“Few people are aware that they are astride the 100 or 500 year floodplain, or what is the meaning of the numbers on the columns and piers, or the speed and power of the flowing water, or how what they observe is part of a grander system. The hydrograph that monitors the river is practically invisible, encased in a box beneath the Marquam Bridge. PDX Marks will bring its information to light.”

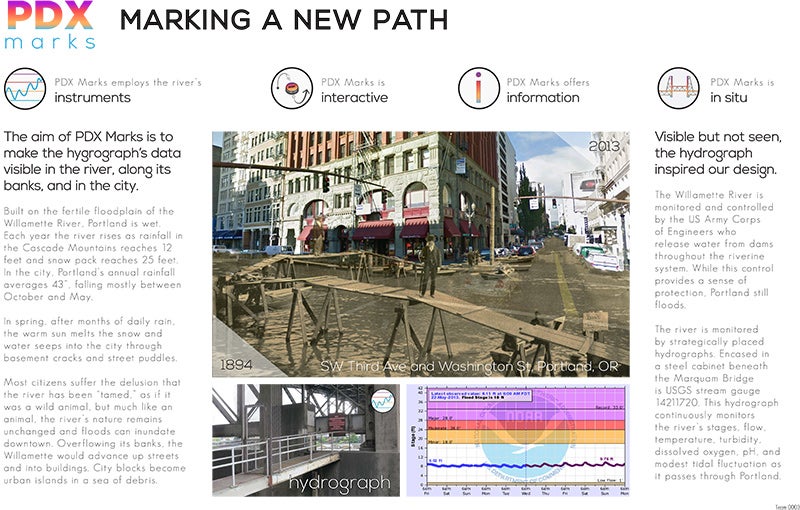

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers monitors and controls the Willamette River using strategically placed hydrographs that continuously monitor the river’s stages, flow, temperature, turbidity, dissolved oxygen, pH, and modest tidal fluctuations. PDX Marks focuses on the hydrograph under the downtown Marquam Bridge.

The aim of the interactive PDX Marks “is to make the hydrograph’s data visible in the river, along its banks, and in the city. Most citizens suffer the delusion that the river has been ‘tamed,’ as if it was a wild animal, but much like an animal, the river’s nature remains unchanged and floods can inundate downtown,” the project states. “Overflowing its banks, the Willamette would advance up streets and into buildings.”

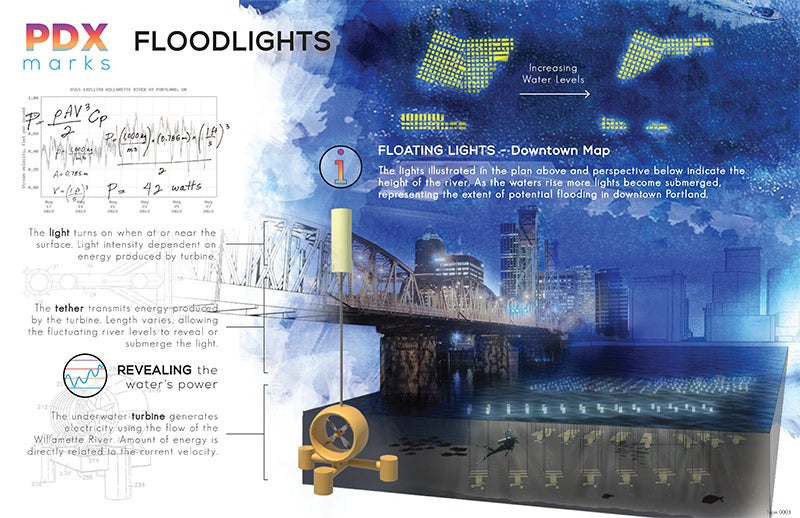

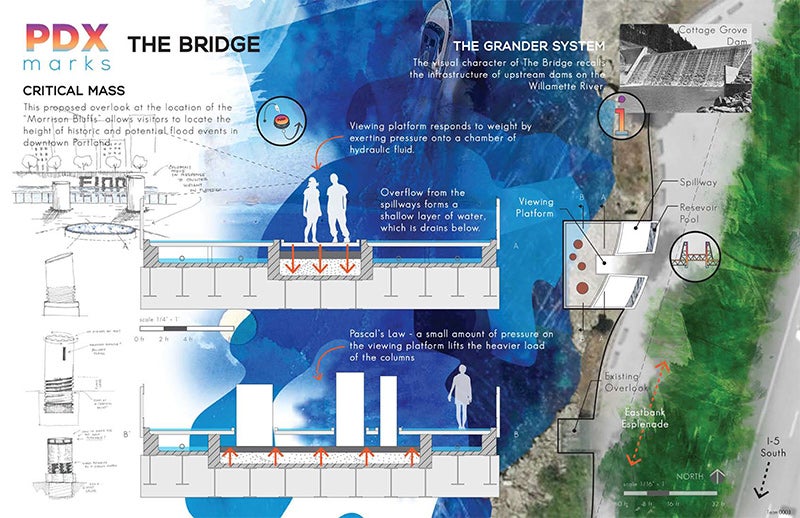

PDX Marks proposes floating lights in the river—as the waters rise, more lights become submerged, representing the extent of potential flooding in downtown. The project also includes a proposed viewing platform where visitors could locate the height of historic and potential flood events. A feature called The Scale would be tethered to the existing East Bank Esplanade and move with the river’s tides, so “visitors could experience being in the river and learn about flood dynamics.” The Scale would also include embedded LED lights literally illuminating flood stages.

The Watermarks competition was sponsored by the University of California Berkeley Department of Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning, Beatrix Farrand Endowment, as part of the observation of the department’s centennial, the Next 100 Years.

The competition was inspired by research demonstrating that members of the public (even well-educated professionals) living in housing developments below sea level in the San Joaquin Delta of California do not understand their true risk of flooding.

“People can buy houses in these developments and are never informed of their true flood risk,” the competition webpage said. “In the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta and along the San Francisco Bay of California, and in the Mississippi Delta of Louisiana, many houses below sea level are not considered to be within the official 100-year floodplain because they are ‘protected’ by a levee. Residents of such a new development in the San Joaquin Delta [reported] that their real estate agents had told them they were ‘not in the floodplain.’ How can we communicate the true flood risk to people living in landscapes where the vulnerability may not be obvious?”

The competition received twenty-seven entries from North America, Europe, and Asia. Winners were chosen by a panel of experts in environmental planning and landscape design: Anu Mathur (University of Pennsylvania), John King (San Francisco Chronicle architecture critic), Georges Descombes (ADM Architects, Geneva), Herbert Dreiseitl (Atelier Dreiseitl), and Walter Hood and Matt Kondolf (UC Berkeley).

First place ($3,000 prize) was awarded to a team from UC Berkeley.

Third place ($1,000 prize) was awarded to a team from Atelier Brume in Paris.

More information is available at the UC Berkeley Next 100 Years webpage.