For many, immigration to the United States is symbolized by Ellis Island and its welcoming of the poor and oppressed from the Old World. While the story of European migration to the U.S. is well known, however, the experience of many Asian Americans is not.

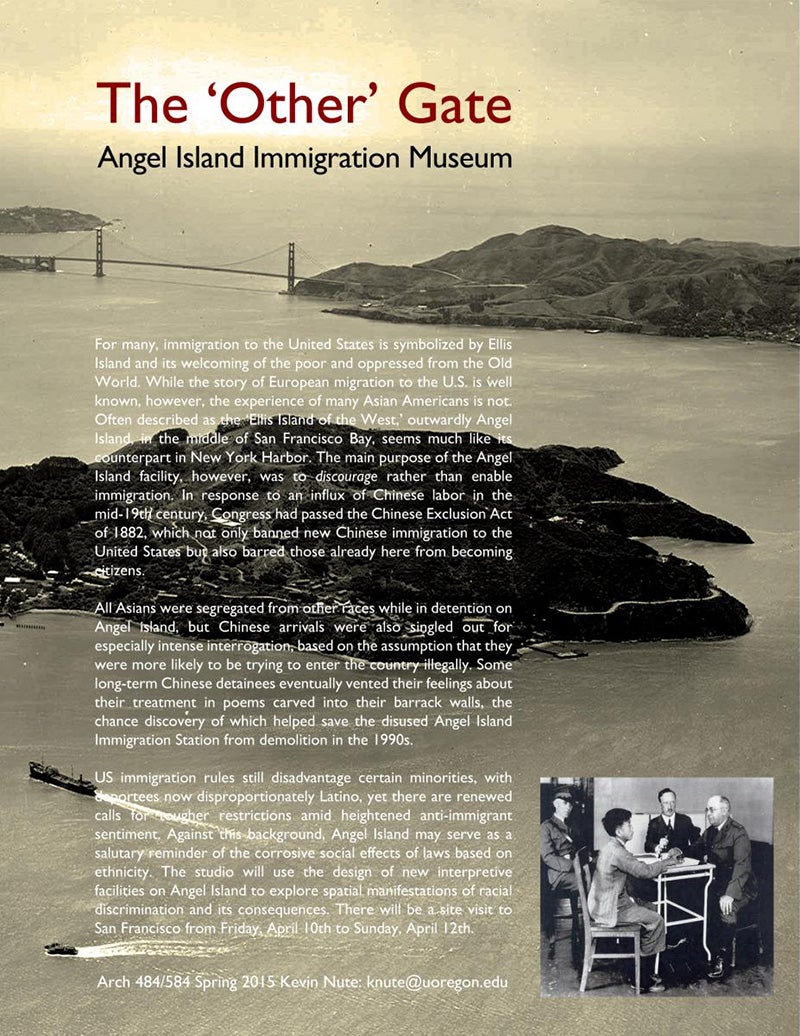

Above: The main purpose of the Angel Island facility was to discourage immigration. Here, a prospective immigrant is fingerprinted before inspectors, who had wide discretionary power in determining the fate of each applicant.

Often described as the “Ellis Island of the West,” Angel Island, in the middle of San Francisco Bay, seemed much like its counterpart in New York Harbor. But the main purpose of the Angel Island facility was to discourage immigration.

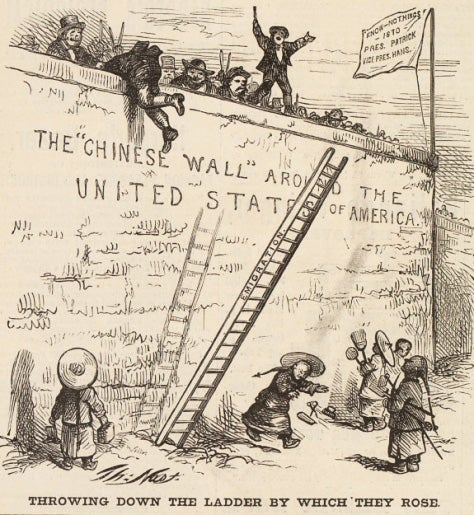

In response to an influx of Chinese labor in the mid-19th century, in 1882 the U.S. Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which not only banned Chinese immigration but also barred Chinese already living here from becoming citizens.

Between 1910 and 1940 Angel Island served as the de facto gate for enforcing the Exclusion Act, with the prime objective to return Chinese who did not have relatives living in the U.S. Most European arrivals at Ellis Island were admitted within a matter of hours, but for many Chinese at Angel Island the process was often extended to months, and in some cases years.

All Asians were segregated from Europeans on Angel Island, but Chinese arrivals were singled out for especially intense interrogation, on the assumption that they were more likely to try to enter the country illegally. Some long-term Chinese detainees eventually vented their frustrations over this blatant discrimination in poems carved into their barrack walls, the chance discovery of which helped to save the Angel Island Station from demolition in the 1990s.

With the support of a grant from the Department of Architecture’s Joel Yamauchi fund, Professor Kevin Nute and a group of architecture students, several of whom are from China, will be investigating how the experiences of Chinese immigrants at Angel Island can best be recalled for current visitors to the site.

“U.S. immigration rules still disadvantage certain minorities, with deportees now disproportionately Latino, yet there are renewed calls for tougher restrictions amid heightened anti-immigrant sentiment,” Nute says. “Against this background, Angel Island may serve as a salutary reminder of the corrosive social effects of laws based on ethnicity.”

To accompany the studio, Chinese American immigration expert Judy Yung, emeritus professor of American Studies at the University of California, Santa Cruz, will present a public lecture, “Angel Island: Immigrant Gateway to America,” at 6 p.m. Wednesday, April 8, in Room 177 Lawrence Hall.

In addition, a visiting exhibition about the Angel Island immigration station, “Gateway to Gold Mountain,” is on display in the School of Architecture and Allied Arts’ Wallace and Grace Hayden Gallery, 120 Lawrence Hall, now through April 9. Both the lecture and exhibit are free and open to the general public.

Above: Angel Island Immigration Station circa 1927, now a museum. Often described as the “Ellis Island of the West,” Angel Island is located in the middle of San Francisco Bay.

Above: A cartoon by Thomas Nast, in the July 1870 Harper's Weekly. In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which not only banned new Chinese immigration to the United States but also barred those already here from becoming citizens.