Asked what Pacific Northwest Preservation Field School project he’s most proud of since the annual projects began twenty years ago, Associate Professor Emeritus and Field School Founding Director Don Peting defers. “That's a Sophie's Choice question,” he says. “It's like your children—you can't isolate and favor any one.”

It’s also impossible to isolate the legacy that Peting alone has had on preservation nationwide. In addition to his work with the Pacific Northwest Preservation Field School—which celebrates its 20th anniversary this year—Peting has served as an architecture professor at UO, had a private practice while teaching, was awarded the prestigious Rome Prize, serves on the State Advisory Committee for Historic Preservation, and continues work as a consultant on preservation projects.

It’s also impossible to isolate the legacy that Peting alone has had on preservation nationwide. In addition to his work with the Pacific Northwest Preservation Field School—which celebrates its 20th anniversary this year—Peting has served as an architecture professor at UO, had a private practice while teaching, was awarded the prestigious Rome Prize, serves on the State Advisory Committee for Historic Preservation, and continues work as a consultant on preservation projects.

His accomplishments are why Peting is being honored in 2014 with the 6th Annual George McMath Historic Preservation Award. The award is presented each year to an individual whose contributions have raised awareness and advocacy for historic preservation in Oregon. Tickets for the award ceremony, May 14 in Portland, are available online through April 30.

The Pacific Northwest Preservation Field School is just part of the legacy mentioned when Peting’s name comes up in the preservation community. A scholar of historic structures and building technology, Peting has studied and consulted on sites as nearby as UO’s Deady Hall and as far away as stone buildings in Oira, Italy. His influence can also be seen in the achievements of graduates of Oregon’s Historic Preservation Program who have gained listings for, and therefore helped preserve, hundreds of sites on the National Register, some as National Historic Landmarks, the highest level of preservation possible.

Other Peting graduates are craftsman and maintenance staff employed by state and national parks, performing the hands-on work needed to physically restore or reconstruct buildings and structures that otherwise would succumb to demolition by neglect. Others serve in jobs as historical landscape architects, architectural preservation planners, Section 106 coordinators, preservation architects, and more. Still others have gone on to become professors themselves, extending Peting’s reach to new generations of preservation professionals.

“More than any educator in Oregon’s history, Don Peting has embedded in his students a caring for and appreciation of Oregon’s historic resources—whether buildings, landscapes, or archeological sites,” says Robert Melnick, former dean of A&AA, professor emeritus of landscape architecture at UO, and former senior program officer at the Getty Foundation. “Beginning in 1963, when he first joined the faculty in the UO Department of Architecture, Don understood the value of historic preservation in contemporary society. As a registered architect, and winner of the Rome Prize, Don set forth to teach his students both the philosophical and technical skills necessary to be advocates and practitioners of historic preservation,” Melnick says.

Susan Dolan (BLA ’94, MLA ’96), program manager for the Park Cultural Landscapes Program in the National Park Service, notes that many UO students have graduated with dual degrees, or at least extensive coursework in preservation, after encountering Peting’s preservation classes as architecture, landscape architecture, or planning majors. "Don has inspired several generations of students to incorporate historic preservation into their design or planning careers, or to pursue historic preservation as a vocation. Don's exceptional talents as an educator, architect, and preservationist have built an exceptional Historic Preservation Program of integrated theory and practical experiences," Dolan says.

Peting taught his students by not just showing them how, but by doing the work himself. His investigations, Historic Structures Reports, and Preservation Guides have informed preservation and restoration efforts and helped secure project funding through private and public grant sources for numerous historic resources in the Pacific Northwest and beyond.

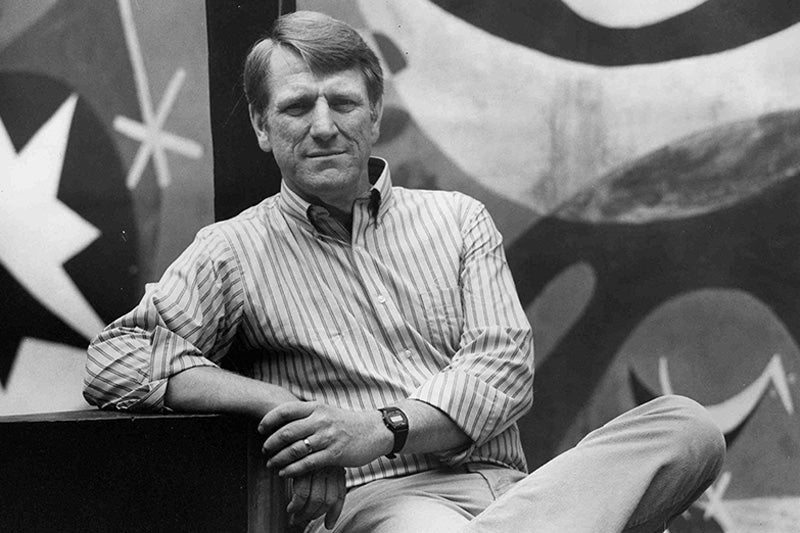

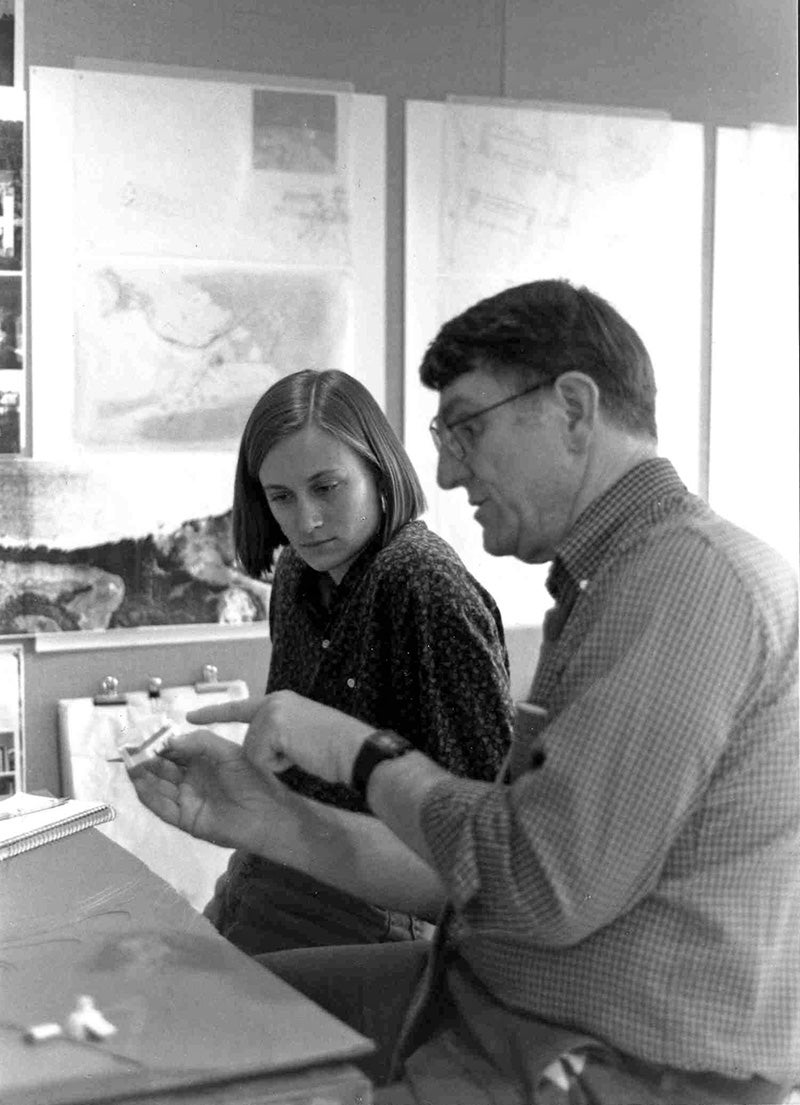

Above: Don Peting early in his career.

As founding director of the Pacific Northwest Preservation Field School, he established a partnership between the University of Oregon and the National Park Service, along with partnerships with State Historic Preservation Offices and State Parks in Oregon, Washington, Idaho, California, and Alaska.

“Many Oregon buildings and structures have undergone preservation, restoration, and/or reconstruction work though the Field Schools due to Peting’s involvement, commitment, and influence, including but not limited to the Cape Blanco Lighthouse, cabins at Silver Falls State Park, Pete French Round Barn, and Officer’s Quarters and Guardhouse at Fort Stevens State Park,” says Kerry Barbero (MS, ‘03, historic preservation), a member of the Springfield Historic Commission in Springfield, Oregon.

Peting’s teaching career, which began at UO in 1963, initially focused on structures and design studio, back in the era when beginning structures courses in the Department of Architecture extended over three terms rather than the one term students now undergo. If that wasn’t enough, he also taught a landscape architecture class.

“I taught eight classes a year,” he says, something no A&AA professor does anymore. Structures “was with the same students for a year—Static Strength of Materials, then steel and wood, all through the one year. I [also] taught studio all three terms.”

After teaching for three years, Peting took a leave of absence, during which he worked full time for an architecture firm in Seattle. “I wanted to get my license and I needed some more training in an architect's office because I had come right from graduate school to here. I was amazed [UO] even hired me” without experience in a firm, he says.

Back at UO as a licensed architect, he taught for several more years before forming an architectural practice with Bill Gilland, former A&AA dean, which was involved with the restoration of Heceta Lightkeepers' House, north of Florence, Oregon. Gilland and Peting Architects operated from 1979-1990.

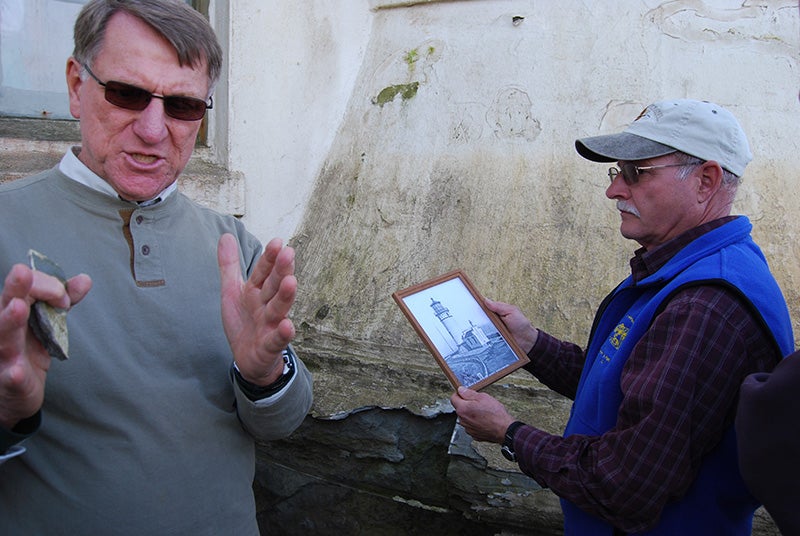

Above: Don Peting works with masonry Instructor Michael Hayden to define the project at the 2008 Field School at North Head lighthouse, Cape Disappointment State Park in Washington.

On a second sabbatical, Peting continued research from his first sabbatical that eventually led to his receiving the Rome Prize in 1977-78 for his groundbreaking research on water mills. His expertise in water mills served students well when, in 2004, Field School took place at Thompson’s Mills in Shedd, Oregon. After student efforts helped stabilize and restore the structure, it became a State Heritage Site.

Peting eagerly involved his architecture students in his water and windmill projects, an early example of UO faculty members’ focus on sustainability. “The green phenomenon is not new, obviously,” he says. “I had a group of students and we built structures that were supported by the wind off the ocean.” Peting also wrote a booklet about wind-supported structures, “Pneumatic Architecture.”

For ventures such as these off the architecture beaten path, he “received a lot of questions from many faculty" who didn’t understand the importance of historic preservation. But he had ample support from other faculty members; in fact his gradual yet continual shift toward thinking “preservationally” was supported, aided, and abetted by fellow professors Philip Dole (“who was certainly my most encouraging mentor,” Peting says), Marian Donnelly, and Mike Shellenbarger, who with Peting spearheaded talks that eventually led to establishing the Graduate Program in Historic Preservation.

“That conversation started in 1979,” Peting says. “The person who really gave the impetus on this was Marian Donnelly; she came back from a conference and said ‘They've got this historic preservation program at Columbia University and we need to start one here.’ “ Columbia had started their HP program in 1975. After many meetings and long discussions and strategic planning, Oregon admitted its first preservation students in 1980.

“We didn't see it as an experiment,” Peting says of Oregon’s Historic Preservation Program. “We saw it as a need.” Yet, though they’d recruited administration support as well as students, he adds, “The main difficulty was that it was the first program in the school run out of a limited slush fund from the Dean's Office.” It would remain that way for many years.

The UO Historic Preservation Program also had no permanent full-time faculty members for many years. Even today, twenty years after its inception, it has just one full-time faculty member, current Director and Professor Kingston Heath, who wasn’t hired until 2004. The program relies on adjuncts, most of whom are program graduates. Current Field School Director Shannon Sardell (’06, historic preservation) began as Field School co-director in 2008 and has served as adjunct professor in a wide range of preservation technology and survey and assessment classes.

As for the Field School, discussions for that first took place in 1994, at a conference organized by a preservation group hoping to grow the HP program. Entitled “Historic Preservation: Theory and Practice," the gathering in Portland drew about seventy people from around the country. “When it was over, we realized that we talked a lot about principles but we didn't share anything about practice,” Peting recalls. “So we decided we needed to teach some aspects of that. And, we decided to do that in a hands-on field school.”

The “we” Peting refers to were Fred Walters, a historical architect; John Platz, a preservation carpenter then working for the U.S. Forest Service; Henry Kunowski, an architect with Oregon Parks and Recreation Department (OPRD), and Peting. All wound up becoming longtime Field School instructors.

But Peting has been the most “steadfast, almost self-less, supporter of [Field School] goals and its students,” observes George Kramer (MS ’89, historic preservation), chairman of the Oregon Heritage Commission. “Don has always been there, teaching architecture and structure to non-architects, crawling through attics and basements on field trips, and providing wise counsel.”

Those field trips were often part of the many sections of “Analysis Through Recording of Historic Buildings” classes that Peting spearheaded and taught each year, often taking students for long weekends or more to sites throughout the Pacific Northwest that needed the help of a cadre of students willing to tackle projects intensively, whether to straighten a sagging wall in a remote barn or to record every building in a company town. These academic-year classes were often a student’s introduction to what the Field School would provide during the following summer.

The inaugural Field School site, in 1995, was the Pete French Round Barn, which had been donated a few years earlier, by the rancher who owned it, to the Oregon Historical Society (OHS). But OHS was never able to take care of historic structures, especially one that was so remote and unique. Knowing that, OHS donated the barn to OPRD, but OPRD was unwilling to accept the structure until it had been stabilized and repaired. “So the field school allowed that,” Peting says.

Located in Southeastern Oregon, the Pete French Round Barn set the stage for what would become a rotation of locations for each year’s Field School. “We decided to take advantage of our unique circumstance here,” Peting says of the Pacific Northwest’s wide-ranging topography. “We've got high desert, mountains, valley, and the coast,” he says, illustrating each with his hands moving up then down, indicating plateau to high mountains to low coastal plain, “so we rotate among all those.”

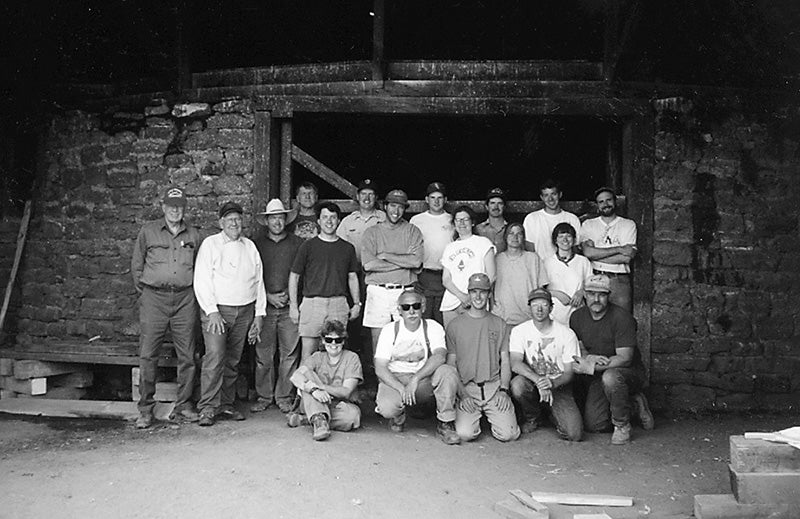

Above: The first Pacific Northwest Preservation Field School was held at the Pete French Round Barn. Students ranged from UO Historic Preservation Program students to state and national parks workers. UO graduates in the photograph include Grant Crosby (front row, center), Dave Pinyerd (second row, second from left), Paul Falsetto (back row, far right) and Alex McMurry (on Falsetto's right). Lisa Sasser (front row, far left), was the first woman to enter the National Park Service preservation trades training program (1984); she worked for NPS in preservation for many years, retiring in 2009. Longtime instructor John Platz is in the front row, second from left. Don Peting is in the back row, far left.

Peting has never been shy about using his connections to enhance offerings for students. He spent one sabbatical year (1984-5) working as a historical architect at Olympic National Park, under the direction of Stephanie Toothman. At the second Field School—in Port Orford, Oregon—Peting invited Toothman for a visit. “Stephanie showed up with [National Park Service historical architect] Hank Florence, and said ‘We can help you with this,’ and the rest is history. As soon as we got connected to NPS, then she and Hank brought in Washington [State Parks], and eventually we included Idaho [State Parks].” (By 2013, Toothman had risen through National Park Service ranks to become Associate Director for Cultural Resources and Science for NPS in Washington, D.C. She remains a staunch advocate for UO’s Field School.)

Fellow faculty members also have played a part in expanding Field School offerings. During the 1999 Field School in Fort Worden, Washington, UO architecture faculty member Michael Cockram came by for a look. As Peting recalls, “Michael said, ‘Don, do you think this would work in Italy?’ I said, ’This teaching is even more exciting with the addition of strong cultural influences.’ The next year, we went to Italy,” where they founded the Italy Field School, which UO offered for seven years, enabled by connections Cockram had in Oira, Italy.

The Field Schools in the U.S. have worked on three lighthouses, several military forts (the oldest dating from the Civil War), Native American sites, Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) park structures, and many differing cultural landscapes. And in recent years, UO has offered the Croatia Summer Conservation Field School. Founded by Historic Preservation Program Director Kingston Heath, the Croatia Field School is an interdisciplinary program that focuses on the traditional stone architecture of Croatia's Central Dalmatian Coast.

Heath praised Peting for his long service to UO and to preservation throughout the Pacific Northwest. “For over four decades, Don Peting has served the University of Oregon as an exemplary teacher, leader, and preservation advocate. He has established a remarkable reputation throughout the Northwest for undertaking state of the art treatment and stabilization projects related to heritage sites,” Health says. “Professor Peting epitomizes the values and intent of the McMath Award.”

Along with the George McMath Award, Peting has been previously recognized with the Preservation Education Award from the Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation in 2006, and the James Marston Fitch Lifetime Achievement Award for Historic Preservation, an honor presented to him by the National Council for Preservation Education in 2005. In 2007, he received the Innovation in Research Award from the University of Oregon.

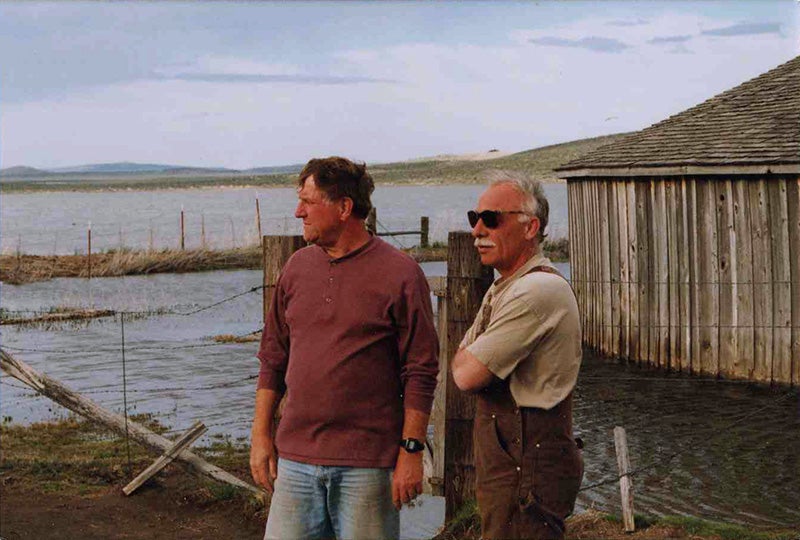

Above: Associate Professor Don Peting and Adjunct Instructor John Platz, a preservation carpenter and longtime field school instructor, visit the Pete French Round Barn in 1994, after flooding inundated the structure. In 1995, the Field School debuted at the barn.

Peting officially retired from the UO in 2002 after serving as director of the Historic Preservation Program for more than ten years. He was appointed to the State Advisory Committee on Historic Preservation and has served since 2010. And he continues to teach and mentor students, architects, and craftspeople as part of the Pacific Northwest Preservation Field School.

In addition, Peting has established two funds at the UO Foundation to support architecture and historic preservation students. The Betty Peting Traveling Fellowship was established in 2007 in loving memory of his wife, and the Pacific Northwest Preservation Field School Director’s Scholarship provides tuition support for historic preservation students to attend Field School.

The McMath Award is well-deserved recognition of Peting’s many contributions to the field of historic preservation in Oregon and the Pacific Northwest, and of his leadership and dedication to education and research at the University of Oregon.

The McMath Award ceremony will take place Wednesday, May 14, from 11:30 a.m. to 1 p.m. at the UO in Portland White Stag Block at 70 N.W. Couch St. Tickets to the award luncheon are $50; proceeds support financial aid for historic preservation students. The reservation deadline for the luncheon is May 3. For more information, please contact Crissy Lindsey at 541-346-2982. Tickets may be ordered online.

Above: At the Thompson’s Mills in Shedd, Oregon, Peting shows students in Field School the nuances of replacing a support post.

Above: Peting sketches out concepts on a plank of wood for students, including Susan Trexler (far right), working on the Officers Quarters during Field School at Fort Columbia State Park, Washington, in 2008.

Above: While much of his Field School efforts take place outdoors, Don Peting is also a popular reviewer for architecture design studios.

Above: Unable to resist investigating historic details even while wearing a suit, Don Peting takes a moment in the Watzek House to figure out the workings of a desk drawer. Assisting is preservation consultant George Bleekman (MS, ’98, historic preservation), author of The Watzek House: A Restoration and Maintenance Plan, which also served as his master’s thesis.