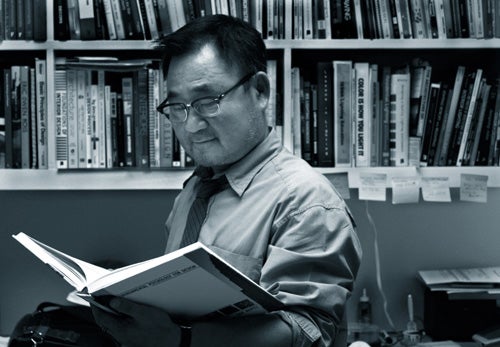

When interior architect Kijeong Jeon, MIArch ’89, was hired to select carpet for a new building in 2008, little did he know the project would lead him to designing “calming spaces” for people with developmental disorders such as autism. Today Jeon, professor and coordinator of the interior design program at California State University, Chico, is recognized as a pioneer in the design of “multi-sensory environments” in the United States.

The project that redirected Jeon’s career was for the Community Opportunity for Vocational Experience (COVE), an organization in Paradise, California, that helps people with autism and other developmental disorders.

The project that redirected Jeon’s career was for the Community Opportunity for Vocational Experience (COVE), an organization in Paradise, California, that helps people with autism and other developmental disorders.

When asked to work on the COVE project, Jeon says, “I’d never heard of autism so I did some immediate research. What intrigues me is that people with autism respond sensitively to lighting, sound, acoustics, tactile sensations, scents – environmental factors. Discovering that, I thought maybe I could make something different” in his program for the COVE. So he began more investigation into autism, its symptoms, and possible treatments.

But his research soon hit a wall. “I found zero case studies about design for a space like this, for autism. I did find lots of articles about autism in medical and psychiatric journals, but nothing in architecture and design professional publications. Most autism research was done in Europe,” he says.

Then he stumbled upon the Snoezelen passive therapeutic system, which originated in the Netherlands in the 1970s. The term is from the Dutch "snuffle" (to seek out, to explore) and "doezelen" (to doze, to snooze). Also called “multi-sensory environments,” or MSEs, Snoezelen spaces are designed to give clients with certain developmental disorders a feeling of serenity and calmness by stimulating their senses in specific ways. MSE therapy helps people with a variety of developmental disabilities, dementia, and brain injuries without treatment with medications or surgical procedures, and is a purely passive therapeutic environment.

Jeon discovered that Snoezelen therapy is so effective for people with autism that more than 1,200 designed MSEs have been created in Germany. That triggered him to dig even deeper to find such places in the United States, which is when he realized there was a research void. His COVE project was just the beginning.

Jeon discovered that Snoezelen therapy is so effective for people with autism that more than 1,200 designed MSEs have been created in Germany. That triggered him to dig even deeper to find such places in the United States, which is when he realized there was a research void. His COVE project was just the beginning.

Jeon’s work as an “autism innovator” is a natural evolution for him, colleagues say.

“MSE encompasses everything Kijeong has been doing both in his teaching and his branded corporate environment work,” says UO Associate Professor Linda Zimmer, who has known Jeon since they were both in graduate school at UO. Along with teaching at Chico State, Jeon has taught at Virginia Commonwealth University and worked as a designer for Group Delphi in the San Francisco area, designing branded environments, trade show exhibitions, event design, and more.

His unique approach into designing for the COVE included personal research to understand how people with autism view the world.

“I try to be that person with autism,” he says. “For example, they like to go behind a sofa and hide, and also cover up with pillows, and then have someone step on their head. They LOVE those kind of things. So I did it myself, put pillows on my head and asked someone, ‘Can you step on me?’ I want to feel how they feel about this, to understand why they enjoy doing this. Experiencing some of what they do helps me learn how I can create an interior space where they can enjoy what they’re doing, and helps me learn what gives them a sense of security or excitement.”

Another example, says Jeon, “is they do this,” he says, producing a large gray comb then staring at it fixedly while his fingers wiggle it. “I tried it myself, asking How do I feel? Why do they enjoy doing this? So I designed one of the walls (of the COVE) from this. We project movies and cartoons on it. The sequence of the movie is similar to the way we’re looking at this moving comb.”

This is an aspect of an autism behavior termed “stiming,” a repetitive motion. This can include flapping the hands or an object with the hands, pacing, thumb sucking, leg shaking, rocking, or head banging, all of which provides a calming effect on the individual with autism.

“A lot of what I did was bringing sensory aspects they enjoy, that makes them feel comfortable, through architectural forms and shapes in an interior space,” he says. “There’s nothing structural – it’s all forms and shapes for psychological purposes. I tried to bring a sense of security through the folds and shapes for this interior space, for example using nonstructural pilasters on the edges to add a greater sense of security than just a regular wall.”

The space he designed at the COVE is not just for users with autism but is also a multicultural, multiuse space for meetings, funerals and other community gatherings. That said, there are spaces definitely geared only for kids with autism, like the Pink Room. He learned that pink and violet are “the most soothing colors for kids with autism. If a kid has a violent episode or other breakdown, they’re sent to this room and within thirty minutes they’re very mellow,” he says. But the color scheme may not work for everyone, he adds. “I can’t stand more than three to five minutes in this room because of the vibration of the colors.”

Jeon is still researching design distinctions that address different levels on the autism spectrum. Meantime, he’s also designing furniture and toys based on his personal experience. He calls one such product the “Wave Bed,” a roughly toboggan-shaped bed where the user’s head lies under the curl, where LED lights and vibrating speakers can stimulate the user’s senses. Jeon is seeking a manufacturer.

Jeon is still researching design distinctions that address different levels on the autism spectrum. Meantime, he’s also designing furniture and toys based on his personal experience. He calls one such product the “Wave Bed,” a roughly toboggan-shaped bed where the user’s head lies under the curl, where LED lights and vibrating speakers can stimulate the user’s senses. Jeon is seeking a manufacturer.

Sites like the COVE that need such products for their clients, along with his successful design implementations to date, are likely to help Jeon find a manufacturer. But in the meantime, his work is already helping a wide range of visitors to the COVE.

“COVE assists individuals who have a variety of sensory needs,” says Bob Irvine, executive director of COVE. “Kijeong’s innovative designs help create feelings of safety, security, calm and discovery for these individuals. I find Kijeong’s design initiatives and his vision admirable.”

Kyu-ho Ahn, assistant professor of interior architecture at UO, brought Jeon to Eugene in January 2013 for a public lecture and to work with Ahn’s students. “There’s a lot of research and vision behind what Kijeong has done, but his work is so beautiful – it’s suitable for the general public,” Ahn says. “That’s a very, very important point. It’s not just something special for these type of individuals, but a design that can be for everybody.”

Sharing his work at the COVE has given Jeon an additional avenue to give back to the community at large, a community different from those he reaches as an educator or, earlier, as a designer in a firm.

“I have designed many other types of projects, but the COVE is the most meaningful and fulfilling project for me,” he says. Paradise, where COVE is located, is a lower middle class community, so most users of the building had never been in an architecturally designed space before; even the contractor had never constructed a professionally designed building. “They were totally surprised by how a space could be this beautiful,” Jeon says. “It’s such a pleasure to share my talent with those who could never afford to experience this type of space otherwise. That my work can contribute to their well-being, can better their daily life, especially for people who may not be able to afford to experience a ‘designed’ environment – that’s a very different feeling” than designing for an airport or corporate brand development.

Recently Jeon created a nonprofit organization, KJMSE (Kijeong Jeon Multi Sensory Environment), for designing MSE spaces for individuals with autism and other disorders. Profits from the organization will be used for design and research for autism-related projects.

More information about Jeon and his work with MSEs is available on his website.

Story by Marti Gerdes