UO students are helping to re-envision a 19th-century Hudson’s Bay Company trading post site to incorporate current fire codes, sustainable materials, and Americans with Disabilities Act requirements—all while respecting the site’s historic character.

Students in two Interior Architecture Program studios in Eugene took on the challenge for three buildings at Fort Vancouver National Historic Site, a National Park Service unit in Vancouver, Washington, during winter 2017.

Above: Sarah Homister’s watercolor rendering of an adaptive re-use of the early 20th century Army barracks. This shows the entry perspective featuring a class field-trip as viewed from the elevator. Image courtesy Sarah Homister.

Taught by Associate Professor Kyuho Ahn and Visiting Assistant Professor Gabrielle Harlan, the two studios shared the overall objective—reimagine the buildings for commercial, retail, and educational use—with slight differences: Ahn’s studio focused more on universal accessibility while Harlan’s emphasized historic preservation.

The students found the studio “really eye opening,” “the most valuable experience thus far in my studies here at the UO,” and “it opened up another career option for me.”

Those comments—from Janet Haselden, Sarah Homister, and Stella Christ—reflect students’ appreciation for the immersion in universal access and historic preservation principles.

“It seemed like a good opportunity to have students work with a real client, to have a project with real constraints as to how the exterior envelope could be altered, and to get exposure to preservation concepts,” Harlan said.

“The students did a wonderful job providing a variety of re-use designs for the buildings,” said Kristen Jontos, business manager at Fort Vancouver, the real-world client for the project. “It is very helpful to have examples of how the buildings could look and function post-renovation to share with interested tenants to help them visualize the potential of the spaces.”

“Historic preservation is not something I would have initially signed up for,” said Homister, an architecture graduate student. “My perspective before this studio was that it is an elitist section of architecture, meant to preserve expensive mansions or significant monuments. After taking this studio, I realize that historic preservation can also tell the untold stories of and remember those marginalized—in the case of this studio, the tribes displaced by the trading company.”

Above: “It was important for me to preserve the history of the building and program it so new activities tell the story of the building’s original function,” student Janet Haselden said. “It is difficult to keep the integrity of a historic building and integrate ADA code.” Image from Haselden’s project portfolio.

Christ, an interior architecture undergraduate, also was initially “hesitant about [designing for] historic preservation, because it seemed like there were so many guidelines that I thought would be restricting,” she said. “But it was incredible to be able to work with those restrictions and guidelines and be able to design a space so intriguing and successful.”

The three early-20th century Army barracks as reimagined by students feature a multicultural center, bicycle repair shop, spaces for dance classes and bird and reptile exhibitions, conference spaces, a contemporary “trading post,” and more.

Their designs also include an elevator, which an early-20th century Army would have spurned.

“I wanted to make every space accessible, which required a careful finessing of elevator and stair relationships to the rest of the space,” Homister said. “I would rather design an average building that is totally accessible than to design a compelling building capable of being experienced by few.”

The studio also introduced the students to two tools used regularly by the National Park Service, which oversees the National Register of Historic Places historic structures reports, which identify historic features in a building, and cultural landscape assessments, which evaluate the physical context of historic sites. The students used the documents to help decide which features must be retained in a building and which could be modified “with proper justification,” Harlan said.

The client, Fort Vancouver, is pleased with the results.

“This was a great collaboration, where practitioners could interact directly with students who are learning their craft,” said Doug Wilson, director of the Northwest Cultural Resources Institute based at the fort.

“I have partnered with the UO through the Pacific Northwest Preservation Field School and now this studio,” he noted. “These projects help to fulfill our mandate of education of students and the public about the sensitive cultural resources that are at the heart of many National Park Service units.”

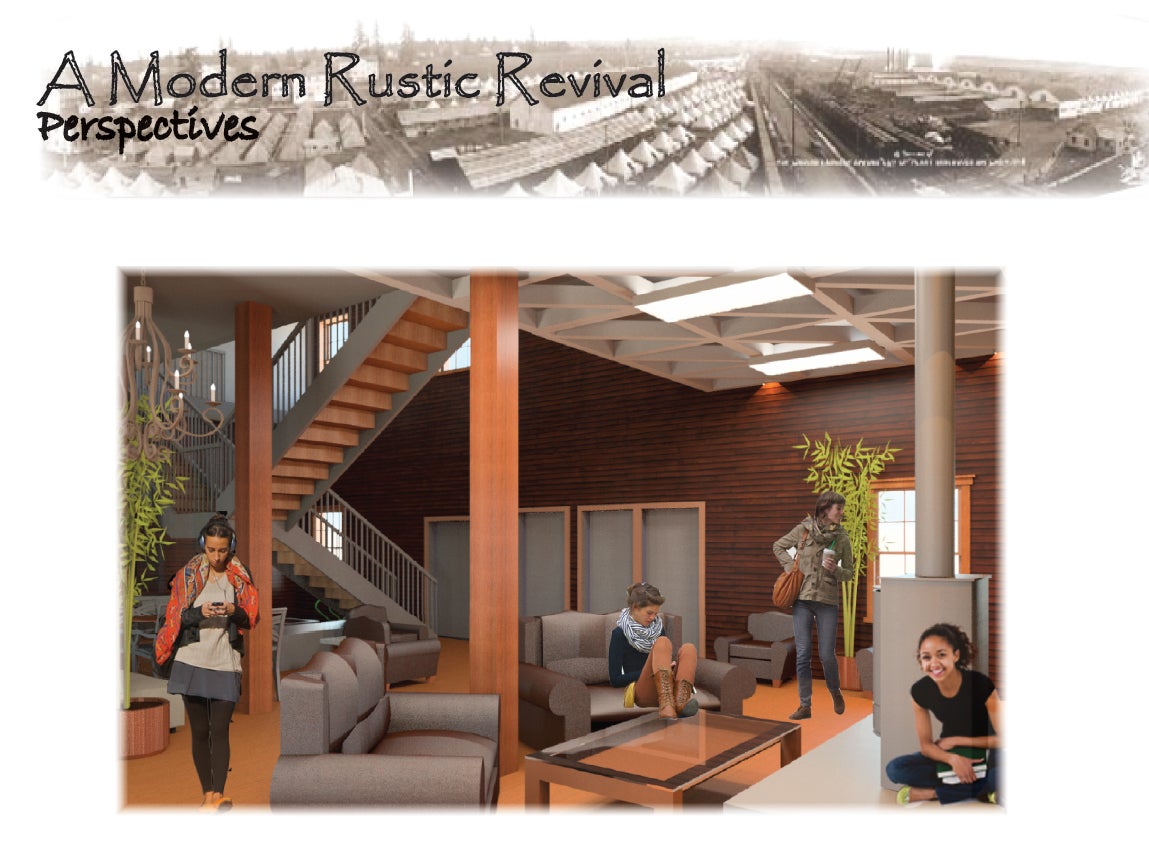

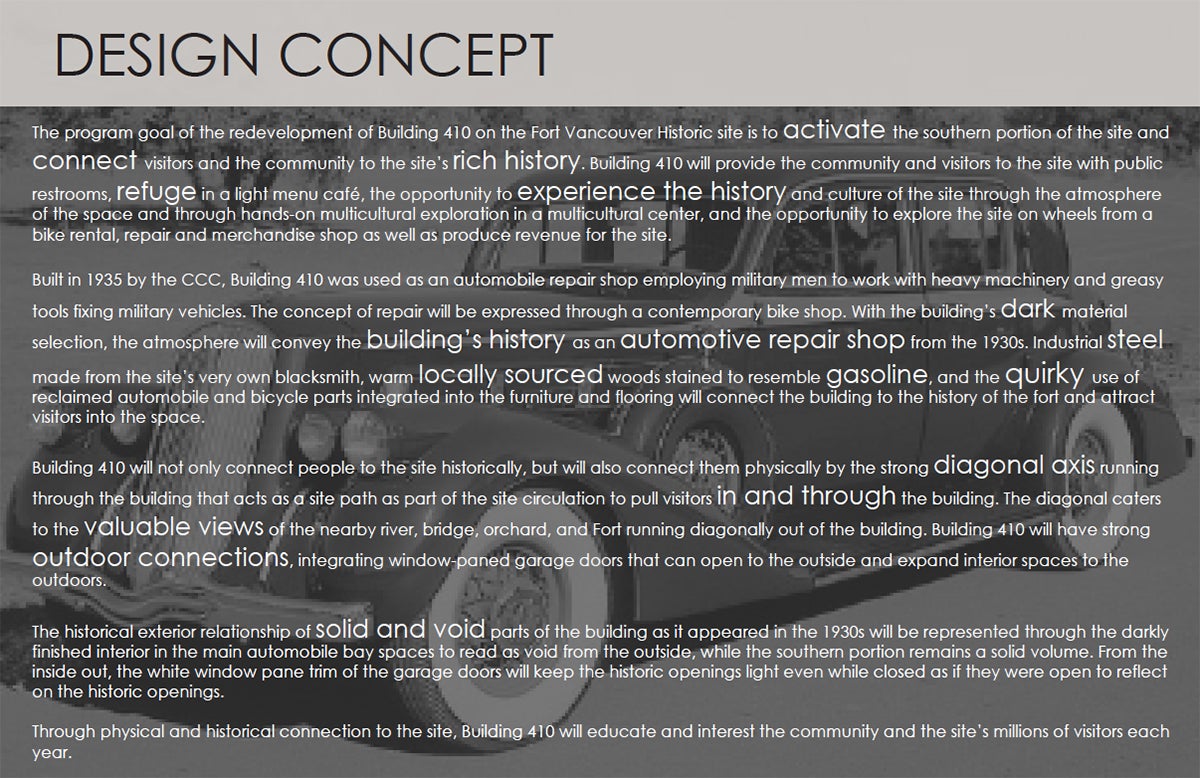

Above: Stella Christ’s programming included a bike repair shop and use of reclaimed auto parts to reflect the historic use of the building for vehicle repair. Image from Christ’s project portfolio.

Above: An explanatory page from Stella Christ’s project portfolio.

Above: Members of the two studios gather at Fort Vancouver. Associate Professor Kyuho Ahn is far right in first row; Visiting Assistant Professor Gabrielle Harlan stands behind him. Photo by Sueann Brown.