Lee Nelson’s terminal project at the University of Oregon School of Architecture and Allied Arts in 1957 was to design a brewery. When he died in 1994, instead of a brewery, Nelson left a national legacy as an American pioneer in historic architecture preservation. He oversaw the meticulous, twelve-year restoration of Independence Hall in Philadelphia. He cofounded both the Association for Preservation Technology International and the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training Center, which named a building in his honor. The U.S. Department of the Interior, home to the National Register of Historic Places program, bestowed its Distinguished Service Award on him in 1988 for his career as a historical architect and preservationist.

Lee Nelson’s terminal project at the University of Oregon School of Architecture and Allied Arts in 1957 was to design a brewery. When he died in 1994, instead of a brewery, Nelson left a national legacy as an American pioneer in historic architecture preservation. He oversaw the meticulous, twelve-year restoration of Independence Hall in Philadelphia. He cofounded both the Association for Preservation Technology International and the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training Center, which named a building in his honor. The U.S. Department of the Interior, home to the National Register of Historic Places program, bestowed its Distinguished Service Award on him in 1988 for his career as a historical architect and preservationist.

Now, working with scholars and archivists at the University of Oregon Libraries, the Historic Preservation Education Foundation (HPEF) in Washington, D.C., has developed a detailed, 60-page annotated bibliography of Nelson’s papers to aid those interested in utilizing the Lee Nelson Collection, which is housed at UO. The collection consists of twenty-six boxes of Nelson’s professional correspondence, architectural drawings, published reports, pamphlets, articles, catalogs, manuscripts, photographs, and slides, most of it generated during his career with the National Park Service (NPS).

“His focus was on the merging of preservation and technology,” says Emily Vance, a former NPS archeologist and current UO historic preservation graduate student chosen for the HPEF-funded internship to prepare the annotated bibliography. “There is just so much in each of the twenty-six boxes,” says Vance, who devoted two school terms to the project. “He was everywhere. Along with projects in the U.S., he had many international ties. He collaborated on projects all over the place – England, Russia, Canada. He was nonstop. He’s an archivist’s dream.”

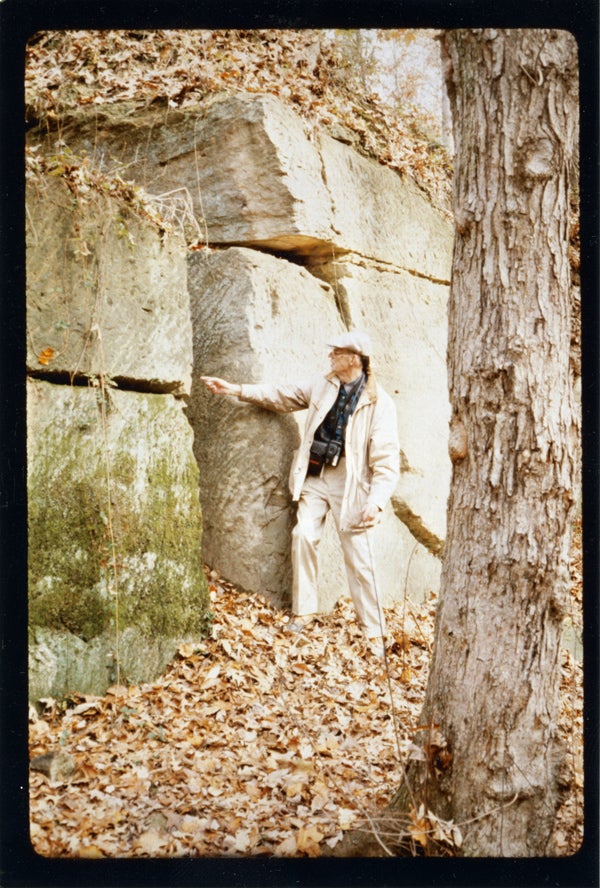

Lee also maintained strong ties with Oregon, working on its many iconic covered bridges and staying in touch with UO professors and students interested in historic preservation. “Oregon was his home,” Vance says.

Born in Portland, Oregon, in 1927, the son and grandson of Norwegian carpenters, Nelson received an undergraduate degree in architecture from the University of Oregon in 1957 and a masters in architecture from the University of Illinois in 1958. That same year he embarked on a lifelong career with the National Park Service, a tenure that helped nurture and shape the historic preservation movement in the United States.

Born in Portland, Oregon, in 1927, the son and grandson of Norwegian carpenters, Nelson received an undergraduate degree in architecture from the University of Oregon in 1957 and a masters in architecture from the University of Illinois in 1958. That same year he embarked on a lifelong career with the National Park Service, a tenure that helped nurture and shape the historic preservation movement in the United States.

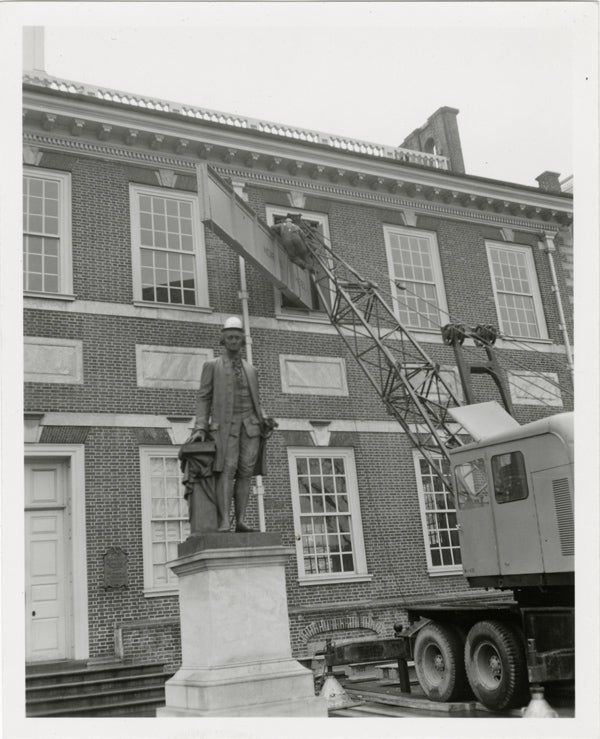

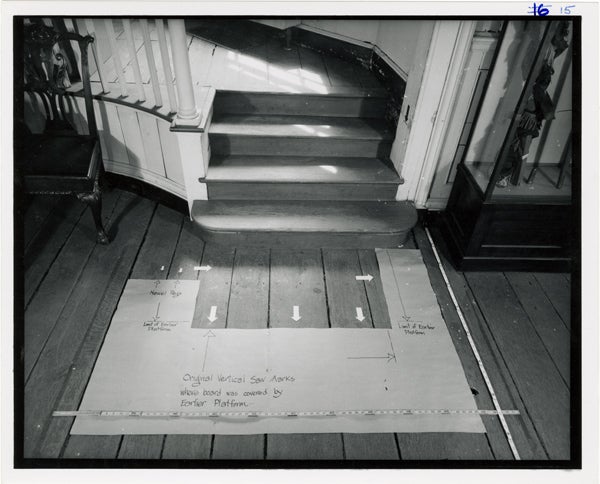

From 1960 to 1972, Nelson worked in the NPS Division of Design and Construction in Philadelphia, where, in connection with America's impending 1976 bicentennial, he led a team to restore Independence Hall, ensuring the building appeared as it did when the Declaration of Independence and U.S. Constitution were written there in the 1700s. In 1979 he became chief of NPS Technical Preservation Services, a position he held until he retired in 1990.

During his years with the Park Service, Nelson helped develop national policies on historic preservation, including promoting the documentation of original building fabric to help determine a building’s historic integrity. Among his many publications are A Century of Oregon Covered Bridges and Historic American Building Survey: An Architectural Study of Fort McHenry. He wrote historic structure reports on Independence Hall and Old City Hall in Philadelphia. His Nail Chronology has served for decades as a guide for dating historic buildings in America. After he retired, from 1990 to 1993 he led the restoration of exterior stonework at the White House, which resulted in his book White House Stone Carving.

Notably, Nelson is credited with developing the idea of the National Park Service’s “Preservation Briefs,” which have become the go-to reference for preservationists seeking help on a slate of projects. The series of technical publications guide the preservation, restoration, and rehabilitation of historic buildings. Topics include improving energy efficiency in historic buildings, preserving historic gas stations, repairing historic concrete, maintaining historic slate roofs, removing graffiti from historic masonry, how to do seismic retrofits on historic buildings “while keeping preservation in the forefront,” and many, many more topics related to historic building and landscape maintenance and restoration.

“Nelson wrote the brief about visual aspects of architecture character, which is a fundamental source when conducting historic surveys,” Vance says. “We've studied it here in my classes and I was using it before I even knew who Lee Nelson was!”

Nelson may have had humble beginnings, but he changed the course of preservation in America, says Robert Melnick, UO landscape architecture professor, former A&AA dean, and the HPEF’s project advisor at UO. “Lee Nelson was an Oregonian, a UO graduate, and a pioneer in 20th century historic preservation. His personal professional papers, now available to scholars through this project, provide a rare and unusual insight into the making of policies and procedures that are still active today,” Melnick says. “It is a major contribution to understanding how and why we seek to protect and preserve architecture that has so much meaning in our lives.”

Nelson may have had humble beginnings, but he changed the course of preservation in America, says Robert Melnick, UO landscape architecture professor, former A&AA dean, and the HPEF’s project advisor at UO. “Lee Nelson was an Oregonian, a UO graduate, and a pioneer in 20th century historic preservation. His personal professional papers, now available to scholars through this project, provide a rare and unusual insight into the making of policies and procedures that are still active today,” Melnick says. “It is a major contribution to understanding how and why we seek to protect and preserve architecture that has so much meaning in our lives.”

Vance, like Nelson, has developed a passion for the National Park Service — so much so that she had the NPS arrowhead logo tattooed on her right forearm. “When you meet other employees in the service, everyone has such a passion,” says Vance, who worked for NPS on habitat restoration and trail crews before moving into more skilled positions. “I wore a lot of hats before I realized cultural resources was what I wanted to do.” At Redwoods National Park, her last NPS job before starting graduate work at UO, she catalogued historic photographs when not out in the field as an archeologist. This summer she’ll work at Death Valley National Park on artifact and building preservation projects at Scotty’s Castle.

In the meantime, Vance is ecstatic to be studying historic preservation at UO, reveling in hands-on opportunities such as the Nelson internship, which she says is “pure archival work, pure research, I love it,” says Vance, who has a BA in anthropology from the University of Mississippi. “The historic preservation program at UO is really stellar. The hands-on aspect is what drew me to it — to be able to do restoration work I need the specialized education. I’m getting that here.”

Shortly after word got out that Vance was working on the bibliography, she began hearing from organizations eager to see the completed product. “People have asked me ‘When you get to this part, send it to me.’ APT (Association for Preservation Technology) is interested in his early correspondence because he was a founding father of the organization. Independence Hall is interested in seeing some of his original notes — he kept a daily journal for every single day while working on the restoration. So there are a lot of different organizations interested in the end result. ”

The UO acquired his collection after Nelson died in 1994. His widow, Lois Nelson, worked with UO Libraries to gift the collection after her husband died. A preliminary finding aid was done, but the comprehensive project that Vance just completed provides a deeper look into Nelson’s legacy.

The UO acquired his collection after Nelson died in 1994. His widow, Lois Nelson, worked with UO Libraries to gift the collection after her husband died. A preliminary finding aid was done, but the comprehensive project that Vance just completed provides a deeper look into Nelson’s legacy.

“I’m putting all of his work into proper context then providing a description of each article he did, of each paper he did, each historic structures report — it’s all focused on him,” she says. “There are a lot of documents by other people but I focus on why he had those. It’s daunting. Some boxes are easy to process and other times it’s stacks of handwritten manuscripts and notes, other times it’s a miscellaneous folder full of Lee’s published articles and who knows what else. It varies from box to box.”

Vance has had ample guidance along the way. She credits Linda Long, manuscripts librarian at the UO Knight Library; James Fox, head of UO Special Collections and University Archives; Jennifer O'Neal, UO historian and archivist; Bruce Tabb, UO Special Collections librarian; her HPEF boss, Chad Randl, a longtime NPS architectural historian now a PhD candidate at Cornell University; “and the slew of student workers who have been so incredibly friendly and helpful,” Vance says. “They've all really helped facilitate this project and gotten it where it needed to go.”

Vance gives a special nod to Lois Nelson for her assistance with the project, for which Mrs. Nelson was happy to lend a hand. “I’m so very pleased that the bibliography has been completed after all these years and can be available to those who are interested in the subjects my husband pursued,” she says.

Vance is also developing an exhibit about the Nelson collection for inside the entrance of Knight Library starting in fall 2013. “She outlined a promising approach to the Lee Nelson material that would showcase a rich collection of personal datebooks, along with period drafting instruments to add three-dimensionality to what will mostly be a two-dimensional show,” says Alice Parman, who teaches “Planning Interpretive Exhibits” in the UO Arts and Administration Program, in which Vance was enrolled spring term. “Emily also developed an exhibit concept that reflects Nelson’s multifaceted and nationally significant career.“

The impact of his career remains wide-ranging. In a letter sent to Nelson’s widow after his death, Martha Aikens, then superintendent of Independence National Historical Park, said of Nelson: "Millions of visitors to Independence Hall each year are the beneficiaries of Lee's work. We continue to use the architectural study collection that he began, the documentary photos that he took, and the note cards that he made. Lee will always be a presence with us, and we will be faithful to his legacy."

The impact of his career remains wide-ranging. In a letter sent to Nelson’s widow after his death, Martha Aikens, then superintendent of Independence National Historical Park, said of Nelson: "Millions of visitors to Independence Hall each year are the beneficiaries of Lee's work. We continue to use the architectural study collection that he began, the documentary photos that he took, and the note cards that he made. Lee will always be a presence with us, and we will be faithful to his legacy."

As for Nelson’s proposed brewery circa 1957, as with his later projects it was painstakingly considered and executed. “It was complete with measured drawings, studied the technical and social obstacles a brewery faces, and attempted to explore solutions in both design, architecture, and the humanization of the process and product,” Vance says. “All the designs and drawings of a practical brewery are there. I like his thinking!”

It’s heartening to know students of the 1950s weren’t that different from students of the mid-2010s. Nelson would have reveled in the Pacific Northwest’s emergence as a microbrewery megastar, but it’s undoubtedly to the betterment of our national cultural resources stewardship that he wasn’t distracted from his destiny.

The annotated bibliography of the Lee Nelson Collection will be available after mid-June at the HPEF website, the UO Knight Library Special Collections and University Archives website, and the Northwest Digital Archives. Along with the annotated bibliography, the websites will include two of Nelson’s audio lectures (to the American Institute of Architects in 1985 and to the Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service in 1980) and numerous photographs.

Story by Marti Gerdes