“A machine is a wetland for parking in.”

The name for the winter 2014 term’s ARCH 484/584 course plays on the aphorism “A house is a machine for living in,” coined by 20th century Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier.

“It’s sort of an inside joke for architects,” said Brook Muller, A&AA associate dean and associate professor in the Department of Architecture.

A typical parking garage is not good for aesthetics, urban livability, or Mother Nature. Muller calls it a most environmentally “problematic” building type. Yet, the paradoxical vision of this studio is to create an operational garage that both serves human needs and directly benefits its natural environment.

Above: Professor Brook Muller holds up a copy of William Morrish’s sketchbook Civilizing Terrains, which contains drawings of archetypes of American landscapes with contemporary architectural models, during the “A Machine is a Wetland for Parking In” studio. Photo by Emerson Malone.

“The idea [behind the course] is that maybe buildings could respond dynamically to biological conditions and needs,” said Muller. “We thought we would take the worst-case offender of urban environmental quality, a parking garage, and see if we could flip it and have it operate in such a way that it could support ecological function.”

Muller’s students learn about adaptive design in architecture. They are asked to create intelligent designs for a forthcoming parking garage in Portland’s South Waterfront district, engineered to ecologically ameliorate the effects of environmental degradation and enrich the immediate environment.

The parking garage will be located near the banks of the Willamette River just west of Ross Island. The 33-acre area is owned by the Zidell Marine Corporation; the site was previously used to build ships for World War II but has since been decommissioned. It will be home to future development that will include condominiums, retail, and lodging.

Designs for the parking garage focus on serving the surrounding natural environment through water treatment, water storage, and water transfer. This construction would ideally work in harmony with its natural neighbors.

Rainwater harvested from the roof of neighboring buildings will be treated and cleaned of any contaminants before being released into the watershed. If the wetlands were in need of replenishment, the intelligent engineering design inherently built into the structure would treat the water and release it to the wetlands.

The parking garage may also use stored water to clean parked vehicles. Motor oils, copper, heavy metals such as lead and other pollutants can be filtered and repurposed for environmental reasons.

“The car gives off things that are awful,” Muller says. “We’re trying to see if we can take this really bad thing, harvest storm water, and possibly put this water to work to create things. Think of a hydrological cycle that includes the motor cycle. Are there ways we can design something primarily for human need in such a way that it does not degrade habitat, but potentially even supports it?”

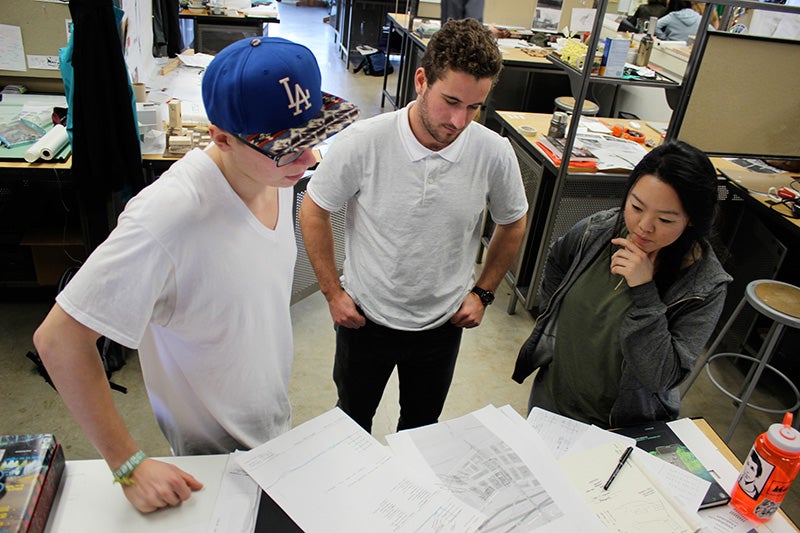

Above: Architecture students (from left) Cody Tucker, Sam Ridge, and Carolyn Lieberman consider their design proposal for the “A Machine is a Wetland for Parking In” studio. Photo by Emerson Malone.

Designs have also been proposed to create a network of buildings linked together to cooperate in the event of a biological need. This could support species’ needs during climatic unpredictability. The goal is to identify biological needs and determine how buildings could behave to adapt accordingly.

Grasslands and wetlands will also be integrated as part of the design of the parking garage. Rooftop grasslands would feature native grasses, wildflowers, and pollinators such as native bees and other insects.

Given the riparian habitat of the river, a wetland-grassland combination would allow for a pollinator prey base for migrating birds, as well as salmon and steelhead in the Willamette. A wetland might typically be thought of as most hospitable to amphibians, but it would be challenging to recondition the land for a tree frog, given the nearby highway separating it from the upland forest.

Graduate architecture student Adam Sitterly has filled his studio desk in Lawrence Hall on the main UO campus with ideas. At the moment, his desk is buried under the vast array of design proposals, sketches, notes, and research materials on the potential sustainability of a parking garage and the salmon life cycle. He jokes that his desk is like geologic layers, similar to the Zidell construction site in the South Waterfront district; his early research lies flat on the bottom where it’s “compressing and hopefully crystalizing.”

He has been investigating—among other things—the parking garage’s water treatment feature, which could treat run-off water and potentially turn around an impressive 2 million gallons per year of clean water.

“We might not be bringing the regional salmon population back to its full levels with this one building, but if we could incrementally work toward these types of aspirational goals, then we are doing our job,” he said.

The irony of transforming one of the most environmentally offensive structures into something of ecological benefit also appeals to Sitterly. If it were possible to turn it into something good for nature, then this bold new prototype would make it easier for future buildings to adopt a greener perspective.

“We’re not just concerned with this one garage at this one location. We are exploring and developing how a paradigm shift could possibly be propagated throughout the design world,” he said. “It would be great if our proposal inspired similar endeavors.”

His team’s design incorporates the aesthetics of the site’s original purpose, as a decommissioning yard for Navy ships. The banks of the Willamette River could pay homage to history and also define the future.

“This is a great studio,” Sitterly said. “This is exactly the reason I wanted to study at this school, and I think that it’s being taught very intentionally and passionately. It balances idealistic aspirations with tangible reality.”

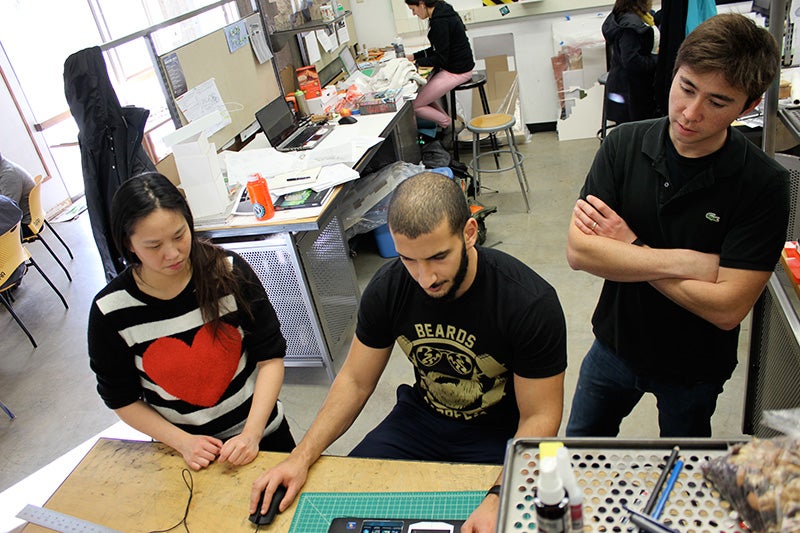

Above: (from left) Graduate architecture students Christina Lin, Mohammad Alboualayyan, and Adam Sitterly consider their design proposal for the “A Machine is a Wetland for Parking In” studio course on Friday, Jan. 31 in Lawrence Hall 379. Photo by Emerson Malone.

The course has had a number of visiting guests and collaborators on the project, including Josh Cerra, a landscape architecture professor from Cornell University, and Mark Wilson, a restoration ecologist who works for the City of Portland Bureau of Environmental Services.

Mark Donofrio, assistant professor of architecture and a structural engineer, works with Muller to assist students in their structural designs and strategies for water storage.

“My involvement with Brook’s studio revolves around that notion of seeking a tectonic polemic in the students’ work,” said Donofrio. “My role … is to provoke the students to seek substantive design solutions, which offer real solutions for change, which are rooted in the technical realization of their projects.”

Colin Ives, associate professor from the Digital Arts Program, has contributed ideas about how digital art can be integrated in the design.

TriMet, the Portland transit organization, is overseeing the planning and construction of a new light rail line that will pass near the parking garage site. Bob Hastings, agency architect for TriMet, also shares responsibility for the project.

Hastings says that he’s impressed with the studio’s direction to engage biological and environmental sciences and engineering with architecture and other design disciplines.

“Typically architecture studios may address building mechanical [or] electrical engineering, but this seems like a more challenging idea, especially in an urban environment” he said. “[The studio] has real potential to create a symbiotic with natural environment systems and inform the public and community in direct and wonderful ways.”

Muller’s forthcoming peer-reviewed book, Ecology and the Imagination, focuses on the issue of adaptive response in architecture. It will be released by Routledge in late February.

Above: A structure resembling three-dimensional bridges in Portland’s South Waterfront District hangs from a studio desk in Lawrence Hall. Photo by Emerson Malone.