In early June, eleven cars from a 96-car Union Pacific oil train jumped the tracks and derailed in the Columbia River Gorge near Mosier, Oregon.

The wreck released oil onto the tracks, sparked a fire that burned through much of the night, and billowed a plume of black smoke into the sky.

This event took place just weeks after the University of Oregon’s winter 2016 term, when UO students in the architecture studio “Lines, Pipelines, and the Contested Space of Fossil Fuel Transportation in the Pacific Northwest” surveyed the region’s transportation infrastructure for coal, oil, and gas. The studio’s aim was to reimagine the future of that infrastructure in the context of global climate change.

“The event in Mosier in the Gorge is not a surprise,” says Associate Professor Erin Moore. “Still, it really reinforces some of the significance of the issues that we were dealing with.”

She adds, “When we started the studio, we were building on existing public concerns in the Pacific Northwest about this issue, and awareness of local communities in danger from international fossil fuel export. Communities in the Northwest, including Seattle, where the oil train lines go right through downtown, have been vocal about this risk.”

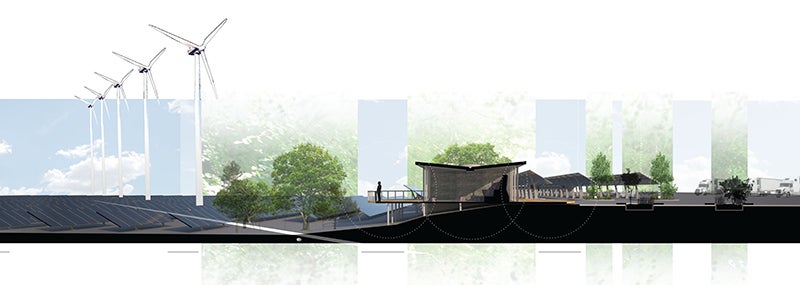

Above: A section from student Ben Llewellyn’s project. Images courtesy of Ben Llewellyn.

Students in the intermediate architecture studio identified the transit system’s effects on the land, assessed human perception of the underground transport of fossil fuels and reimagined the infrastructure as a whole. This led to an array of approaches, including designs for worker and environmental safety for oil train employees in the Gorge and proposing alternative uses for the infrastructure in a renewable energy economy.

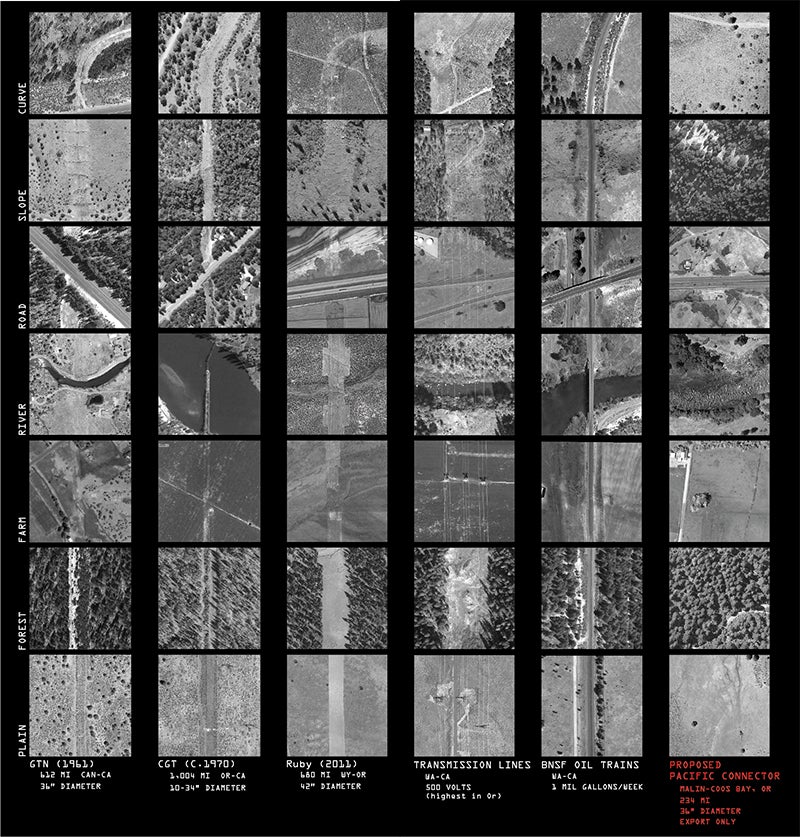

The studio was partially inspired by the proposed construction of the Pacific Connector pipeline, an underground 232-mile conduit that would transport liquefied natural gas from Malin, Oregon, through southern Oregon and on to Coos Bay for liquefication and shipping to Asia.

The pipeline, fiercely contested by climate activists and by some affected landowners, is a source of controversy because the 36-inch pipeline and 100-foot wide easement would require clear-cutting through public and private forests, digging under a number of rivers and streams, and crossing private land.

For his project in the studio, graduate architecture student Erik Wadman looked to a route of an existing pipeline route that crosses from Nevada to Washington and considered the natural habitats that were transformed to make way for the fossil fuel transit.

Wadman says his project looked to the future of the energy economy, as humans move to alternative sources and away from inevitably obsolete fossil fuels. The project proposed transforming existing clear cuts over natural gas pipelines into habitat corridors that create transportation links between disparate plant and animal populations.

“It was a way for me to think about how our nation invests in infrastructure at a different scale,” he says. “We spent a long time in the studio framing the problem, and I think that we had more compelling and interesting designs because of that.”

“The kind of hubris of that proposal, that we propose doing something so radical was really eye-opening,” says Moore of Wadman’s project. “While the idea of cutting a swath of infrastructure across a community seems crazy, his proposal to make a huge investment in connected wildlife habit is no more radical than putting a pipeline across the state. And it would probably do a lot more good.”

Above: Llewellyn says his rest stop design, as show in this rendering, is intended as an alternative to the pipeline, which would alleviate the indifference between humans and the energy they consume.

Prior to the studio, Wadman says he hadn’t really considered the Pacific Northwest’s role in the global fossil fuel trade.

“The Pacific Northwest has a reputation in America for being ahead of other regions environmentally, and I think that this could be an opportunity to take a leadership role and try to stop some of the fossil fuel infrastructure from coming in,” he says.

Visiting Fulbright PhD scholar Iryna Volynets attended the studio as a visiting critic. Moore says Volynets’s Ukrainian heritage offered an outside perspective that allowed the class to think about the international implications, as Volynets’s home country of Ukraine has a somewhat comparable role to the Pacific Northwest — it’s also a territory interwoven with infrastructure for fossil fuel transport.

Above: For his project, Llewellyn observed the physical imprints left by the pipelines, power lines, and rail lines. He designed a series of rest areas installed on wind and solar farms that would power electric cars.

“It helped us realize that this is an issue that has parallels in Europe,” says Moore.

Undergraduate architecture student Ben Llewellyn says that although the studio maintained a regional focus on the Pacific Northwest, its scope was as wide as the international fossil fuel industry. He says the studio made him think about an emotional detachment humans have with how their gas goes from underground to fuel injection.

“That was the focus of the studio – bringing to light what’s invisible,” he says. “People like myself don’t know how to gauge the amount of energy they’re using or how much we’re wasting. Our disconnect from the production of energy pushes our lack of understanding about our own energy.”

For his design, Llewellyn conceived of a series of rest areas installed on wind and solar farms that would power electric cars. He says his rest stop design is intended as an alternative to the pipeline, which would alleviate the indifference between humans and the energy they consume.

“Pipelines are underground. Nobody interacts with it or knows what’s going on with it,” he says. “[The rest areas] could be a way to bring people into the infrastructure and have them be a part of it and learn about it. This could get people interested in the creation of their energy.”

Wadman agrees on the importance of getting people interested, and informed, about the realities and consequences of energy production. The “hundreds of miles of natural gas pipelines [that] course through the nation [deliver] an ultimately unsustainable product,” he says. “While the midterm threat of a warmer planet and the need to phase out fossil fuels is well known, the long-term threat of reduced biodiversity is not as well understood.” His Oregon Habitat Corridor project, he notes, “makes the argument that natural gas should be swiftly phased out and replaced with habitat corridors using the existing clear cuts and right of ways.

“The disconnected environment, cordoned by human developments, is a completely unprecedented planetary shift,” he adds. “Wildlife desires these corridors as means to mate with distant populations, build their genetic pool, and continue the process of evolution. These near-wilderness connections cut through farms and cities at incredible expense, representing a shift in core values for how humans should live.”

Further student work from the “Lines, Pipelines, and Contested Space” studio, including designs from Stephanie Morales, Jordan Frazin, and Susanna Davy can be found at the Sightline Institute website.