The basking shark has a unique anti-clogging filter-feeding process

The basking shark has a unique anti-clogging filter-feeding process

A year ago, Julia May (MArch I, 2019) and Alex Balog (MArch I, class of 2020) didn’t know much about the basking shark—or each other.

Much has changed. In November, they traveled to San Diego for the Landscape Extreme Design Challenge at the 2019 American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) conference. The two were finalists in the competition and presented their design for the biomimetic Basking Filter.

In late October, they attended the Ocean Exchange conference in Fort Lauderdale, where they were finalists for the Broward Collegiate Award for innovations that align with the United Nation’s sustainable development goals while creating economic value.

The story of May, whose graduate and undergraduate work was rooted in architecture and Balog, who comes from an environmental engineering background, and the basking shark began when the students met winter term 2019 in the Biomimicry and Parametric Design course (ARCH 410/510) taught by Nancy Cheng, an associate professor and head of the Department of Architecture.

The course examined how using designs modeled after nature can address environmental challenges.

May and Balog hadn’t really spoken to each other during class, but May asked Balog if he’d like to work together on the course’s major design project, which tasked students with identifying an organism, abstracting its function, process, or system, and translating it into an architectural form or design element that could solve an environmental problem.

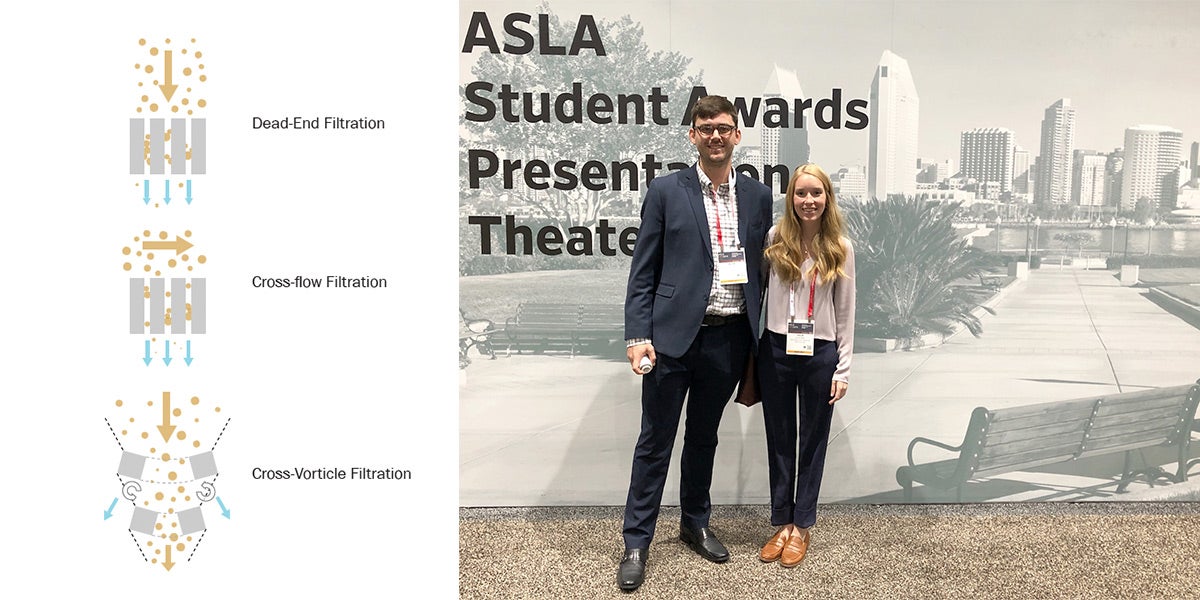

Dead-end and cross-flow filtration are the main types of filtration systems, whereas the basking shark has a cross-vorticle filtration system; Alex Balog and Julia May at the ASLA conference in November

Dead-end and cross-flow filtration are the main types of filtration systems, whereas the basking shark has a cross-vorticle filtration system; Alex Balog and Julia May at the ASLA conference in November

Filtration was a topic that both May and Balog were interested in because of its potential environmental impacts, and May uncovered a research paper from College of William and Mary’s Biology Department that outlined the basking shark’s unique anticlogging filter feeding process.

As Balog explained, filters, whether for air or liquids, need to be cleaned or replaced.

“It takes time, money, and can be hazardous,” he said.

“In architecture school, we’re often faced with environmental problems, especially when it comes to water and air quality. Cleaning them up usually involves some kind of filter,” May added over the phone from Seattle, where she is interning at The Miller Hull Partnership architecture and planning firm. “We found a biological form that was unique in the sense that it had anticlogging capabilities.”

Anticlogging filters using this specific technology, they explained, don’t exist on the market currently.

So, beginning in class and continuing on as independent research, May and Balog designed a filter for water treatment, modeled after the basking shark’s biological system, to address water pollution in the event of combined sewage overflow as well as increasing efficiency of an existing facility. The basking sharks’ jaw creates vortices that continuously flush out its gills, which “provides the backbone for the self-cleaning filter.”

As May and Balog wrote in their project report, “Swimming with its mouth wide open, this fish catches plankton on the side of its gills. Water eddies around the gills, pushing the plankton back into the main flow, which sends suspended food toward its digestive system. The eddies create a self-cleaning effect like backwashing that turns this ‘sluggish, inoffensive fish’ into inspiration.”

This system can be used in current drinking and wastewater treatment plants, extending the life of filters and lowering maintenance costs. The technology has the potential to be applied in other applications, “like panning for gold,” to catch desirable materials as well.

While the concept was solid, Balog explained, the design took trial and error. For the class, the team submitted their first official report on the filter to Biomimicry.org.

“We did not do very well, but we didn’t stop.” Balog recalled. “It is the perseverance and belief in our ideas that kept us going, rather than outside validation.” Balog adds that they didn’t win first place at the Ocean Exchange conference either, but they will keep pushing forward with the design.

A key part of fine-tuning the concept, May said, was soliciting feedback during the class about the design’s application from professionals such as John Breshears, a senior building scientist in Portland. And Cheng was an advisor for the independent research. Balog called her a spiritual guide in the process.

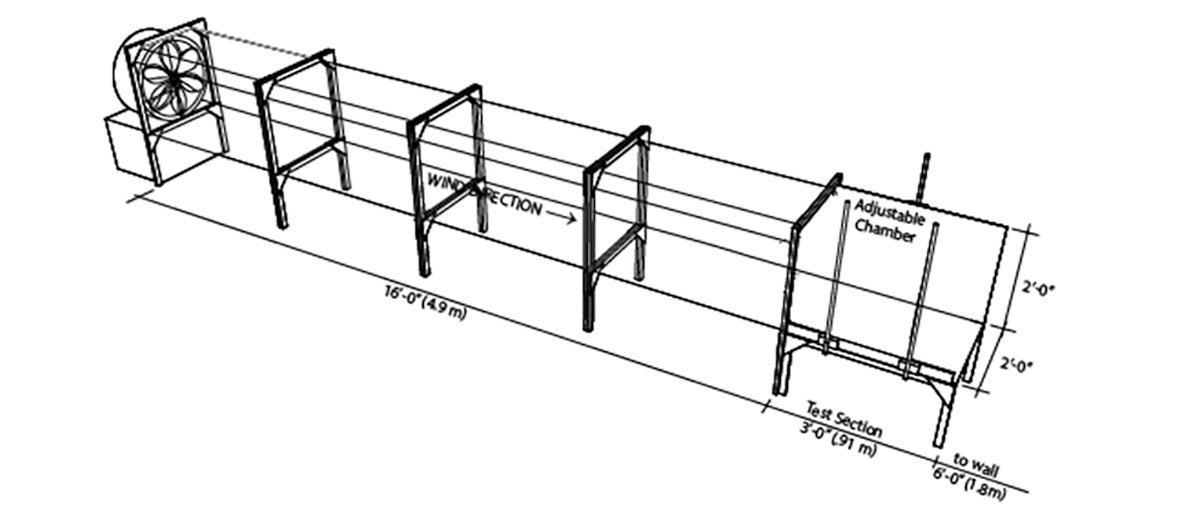

They also used the Energy Studies in Buildings Lab (ESBL) as a resource. Using the lab’s wind tunnel, they tested to see if the filter design could scale up as well as adapt to different fluids by simulating fluid movement.

A diagram of the Energy Studies in Buildings Lab wind tunnel that the team used to conduct qualitative tests for the filter design

A diagram of the Energy Studies in Buildings Lab wind tunnel that the team used to conduct qualitative tests for the filter design

“In this successful partnership, Alex Balog provided background on water filtration context and pieced together important parts of the presentation. Julia May created the interpretive hand drawings and provided the drive behind ruthless editing with a vision of how to create a truly top-notch product,” Cheng explained. “Their ability to engage experts as consultants and build a successful collaboration is a great model for designers in the 21st century.”

And while May and Balog did not win the ASLA or Ocean Exchange award, they said it was a great opportunity to network, present, and share their message:

Cleaning the environment is imperative to our health, Balog and May wrote. The Basking Filter “fulfills the triple bottom line of supporting social issues (e.g., human health and conservation), the environment, and the economy.”

Update: Balog is now working with Oregon State University to develop a prototype.