Thanks to four years of transnational efforts by UO in Portland architecture students, the first two buildings of a new campus for Ukrainian Catholic University (UCU) recently opened near the historic center of Lviv in western Ukraine.

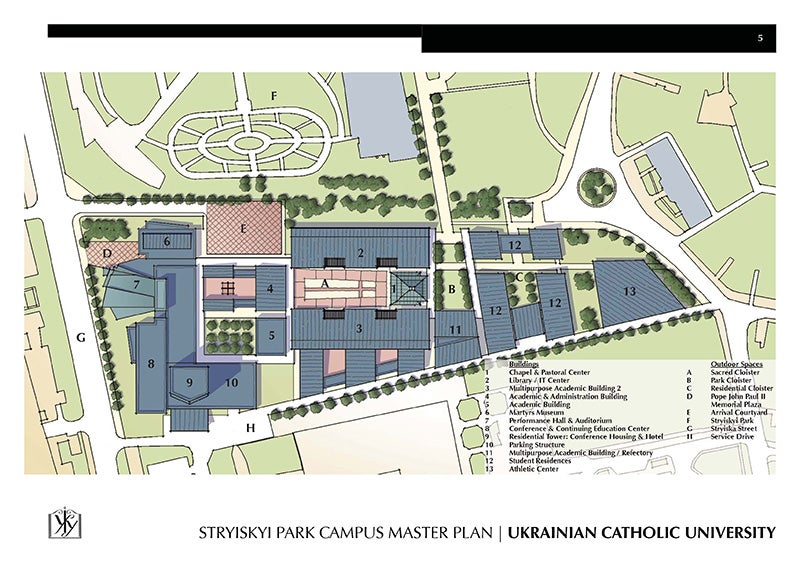

UO architecture Associate Professor Gerald Gast and graduate students from the Urban Projects Workshop of the Department of Architecture in Portland developed the master plan for UCU’s new Stryiskiyi Park campus.

“Ukrainian Catholic University is significant because it is the first Catholic university on the territory of the former Soviet Union,” Gast says. “It stands as a free, independent model of university education in Ukraine. The new campus site was dedicated by the late Pope John Paul II in 2002 when he visited Lviv. The university has a strong base of financial support from around the world.”

Above: The Ukrainian Catholic University (UCU) campus in Lviv, Ukraine, as envisioned by the master plan developed by students in UO’s Portland Urban Projects Workshop. “Spending two years at U of O's Portland program prepared me to better understand and work at the scale of a city as an architect. Portland is a city unlike any other and its density offers great work opportunities in the field concurrent to your studies,” says Jonathan Lemons, now a Seattle architect who as a student helped draft the UCU master plan. Image courtesy Gerry Gast.

Lviv reflects Polish, Hapsburg, and Russian heritage. With a population of 800,000, the city is a longtime center of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic rite, which is central to UCU. Founded in 1928, the university was closed by the Soviets in 1945 and reopened in 2002 following Ukraine’s independence.

The UO students’ master plan envisions the UCU campus “as a procession of cloisters and courtyards. The Church is the centerpiece of the central cloister, ‘The Sacred Cloister,’ and of the campus as a whole,” the UCU Campus Master Plan states. “The spatial idea of the cloister is derived from the ancient monasteries of the Christian world, although its precedents reach back to the Classical architecture of the Greek Agora and Roman Forum. Near Lviv, the Monasteries at Univ and Krekhiv provide historical precedents. Although these historic buildings were influenced by the need for protection, the spatial order of the cloister serves a modern purpose by defining a religious community within the surrounding city of Lviv.”

Professor Gast and students designed the campus plan to have a formal and unified order, although not a rigid symmetry. “The University campus simultaneously focuses inward and outward,” the master plan states. “The cloistered plan creates a serene and contemplative environment protected from the distractions of the city. At the same time, its spaces and buildings engage the city, communicating the presence and importance of the University mission to the outside world.”

Gast’s connection to UCU came via John Lucero, a colleague at Stanford University. “John is an educator with experience in real estate economics who helped [UCU] formulate its space program,” Gast says. “UCU had just acquired an 8-acre site for a new campus donated by the city of Lviv. This, and an existing high school structure in the city center, was a replacement for the properties lost” in 1945 when the Soviets closed the original university and confiscated university buildings in Lviv’s city center.

As Gast and Lucero discussed possibilities for the newly donated site with UCU officials, they soon realized a strong master plan was the first priority. Gast offered to provide his time pro bono, with additional assistance coming from UO architecture students in the department’s Portland Urban Projects Workshop.

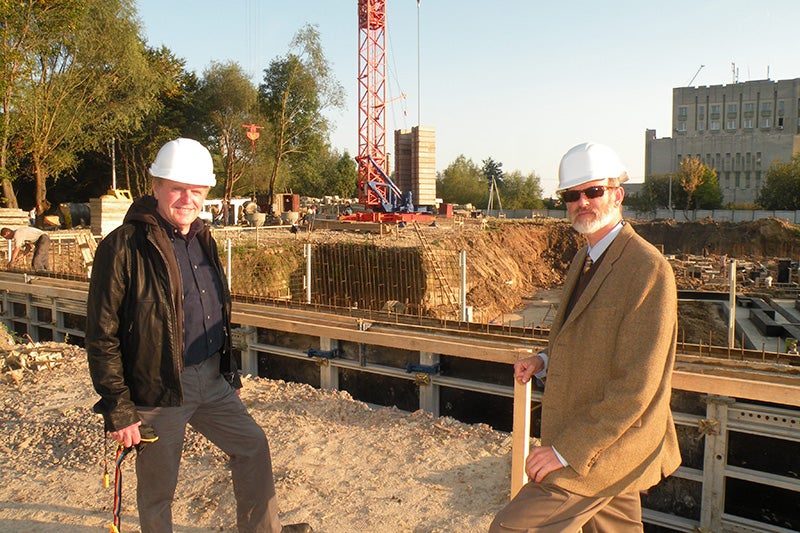

Above: Associate Professor Gerry Gast (left) and Jeffrey Wills on the site during construction at UCU. Wills, a former University of Wisconsin professor who has served as vice rector for Planning at UCU, came to Portland to meet with UO students working on the project.

The Portland Urban Projects Workshop was founded in 2002 to provide advanced UO architecture students with opportunities for immersion in research, public architecture, and urban design projects. The Workshop provides professional services supervised by experienced faculty and staffed with graduate and advanced undergraduate students.

Gast and his students began working on the UCU master plan in fall 2008.

“We started with a student team of five graduate and one fifth-year student,” Gast says. “One of the students, Jonathan Lemons, and I traveled to Lviv in fall 2008 sponsored by the university through its contributors. The master plan was prepared during the following eight months and presented to the university and public in Lviv in June 2009.”

Lemons, BArch ’07, says “it was a once in a lifetime experience to help kick off these efforts with Gerry and be a part of this team.” Having attended a United Nations World Urban Forum a couple of months earlier, “I wanted to help make a positive difference for an architecture project outside the U.S.,” he says. “Gerry had approached me with the unique opportunity to make [the UCU] project the focus of my honors college and architecture thesis with him and to help lead his team. Less than a few weeks later, Gerry and I flew to Ukraine together, we began working with a great team of people, and I was experiencing the cultural histories of Central and Western Europe for the very first time. We arrived shortly after the Orange Revolution and hopes for the future were very high for Lviv's citizens.”

(Lemons wound up living in Lviv to continue work on the UCU project, then moved to Budapest to work for a firm based in the Netherlands. Now a project architect at HyBrid Architecture + Assembly in Seattle, Lemons is a registered architect and holds AIA, NCARB, and LEED GA designations.)

Another group of Portland students joined the effort the following academic year. Over the next three years, in addition to continuing work on the master plan, three students designed university buildings as thesis projects. As student teams changed over the four years, Gast coordinated the effort and continued work with the university on the master plan and architect selection. The students’ concepts were used by UCU to develop programming and design options.

Gast also helped select the initial architect for work on the Stryiskiyi Park campus.

“For the first two buildings, the university wanted to hire an American or western European architect for the work,” Gast says. “A local Ukrainian firm handled permits and construction coordination. At the university’s request, I prepared an architect RFP and a selected list of firms to invite. Kallmann McKinnell & Wood (KMW) of Boston, who has considerable experience in higher education buildings, was selected.”

As for his students’ efforts on the project, their work “has taken place in Portland with regular communication of drawings and other documents by Internet, then presented in person in Lviv,” says Gast, noting that “I’ve carried many models on planes.” The students also had the opportunity to meet in Portland with Jeffrey Wills, a former University of Wisconsin professor who has served as vice rector for Planning at UCU; he came to Portland in 2010 to meet with UO students.

UO student participants in the UCU project have included Chris Chu, David Donaldson, Adam Franch, Nathan Gregory, Yeosine Huggins, Jonathan Lemons, Adrienne Leverette, Steven Miller, Kevin Montgomery, Daniel O’Toole, Michelle Hyun-Jin Pak, Samantha Polinik, Andres Seminario.

Gast and UO graduate students continue work on the campus development, advising the university on architect selection, programming, and building design.

“This process is ongoing,” Gast notes. “The campus will take fifteen to twenty years to complete, depending upon funding. I’ll be returning to Lviv in June of this year, assuming political conditions are stable. Two additional buildings are in design development and scheduled to start construction soon.”

Above: Rendering of the student residences, by KMW Architects. Image courtesy Gerry Gast.

Gast has high praise for his colleagues at UCU. “The UCU faculty are an extremely talented and highly educated group. Most have PhDs from distinguished western universities such as Harvard, Yale, Cambridge, and Heidelberg. The rector (president) is a Harvard PhD in philosophy and divinity. In my thirty years of practice, the faculty and university officials at UCU are the most astute, dedicated, and highly educated people I have ever worked with.”

The current political and economic turmoil in Kiev, located approximately 300 miles from Lviv, has not directly affected the UO work with UCU, however a 28-year-old UCU history professor, Bohdan Solchanyk, was killed by a sniper on a visit to Kiev in late February.

“It seems we got a chance from God for a new country. I can hardly believe it. But the price is very high,” UCU Vice Rector (provost) Taras Dobko wrote to his UCU colleagues—including Gast—to inform them of Solchanyk’s death.

“Now we in Ukraine have much work to do,” Dobko continued. “We must not miss this chance to turn Ukraine into a normal country. It will be difficult. But I see hope in the fact that now many people share the slogan of [the] Solidarity movement in Poland: ‘Nothing about us without us.’

The UO students’ efforts to help “turn Ukraine into a normal country” can be viewed online in a PDF of the completed master plan.

Above: The nearly completed student residences on the UCU campus.