A year ago, Menna Agha would peer out her downtown Eugene apartment window and watch the scene below. In rain or shine, unhoused and disenfranchised citizens of Eugene would gather in the parking lot below, looking for food, shelter, and community.

According to 2018 data from the Department of Housing and Urban Development, Eugene has the highest per capita rate of homelessness of any U.S. city.

“For this community, which is disenfranchised, they don’t have the right to have an experience of housing in the city they live in,” said Agha, an architect and Design for Spatial Justice Fellow teaching architecture in the School of Architecture & Environment. “Isn’t it justice that this city would be everybody’s house?”

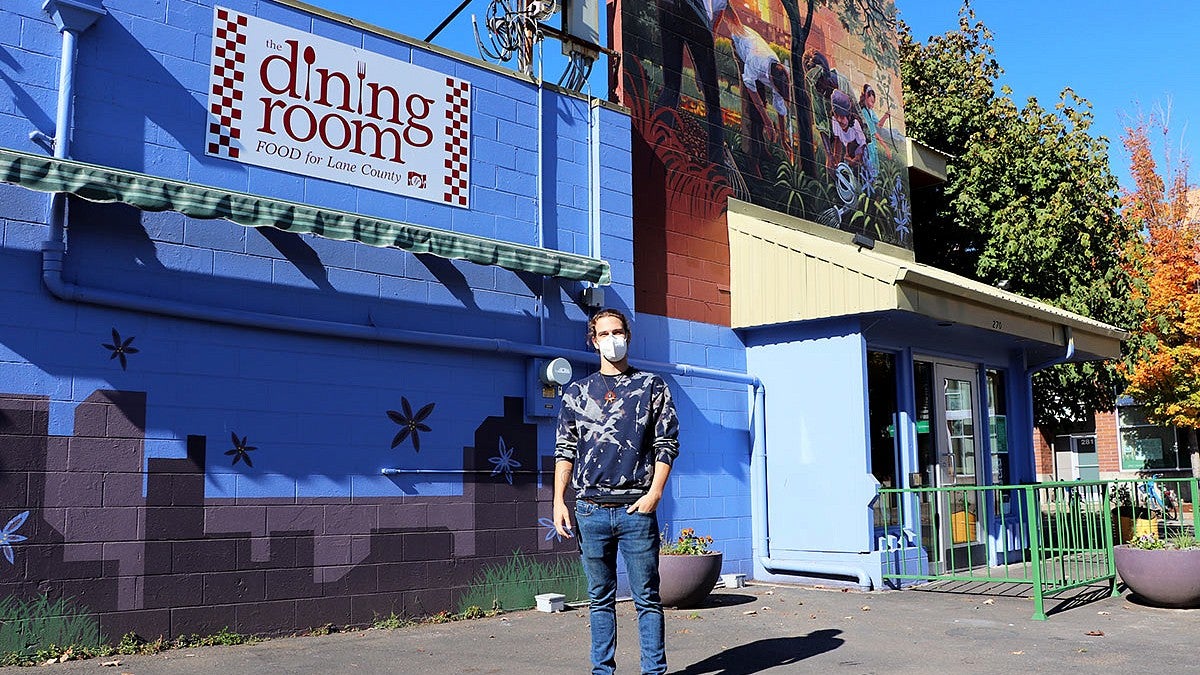

The parking lot belongs to The Dining Room, a restaurant run by Food for Lane County, a nonprofit food bank. Before COVID-19, community members would wait in the parking lot for a seat to open up in the restaurant with a capacity of 30. Now, because of COVID-19 restrictions on indoor gatherings, people must wait in line to pick up meals to go in the parking lot.

During the past year, through architecture studios, the “City is a House” design-build project, and much volunteer work by students, The Dining Room parking lot is now home to three “hoppers,” or movable shelter structures on wheels, upcycled adaptable seating, a freshly painted mural, greenery, and a newly planted tree. An outdoor sink and sanitation station will be completed in the coming months.

“This project has been a gift from heaven,” said Josie McCarthy, the program manager for The Dining Room who partnered with the design build team. “The parking lot was always a problem, but I didn’t have the money.”

In fall 2019, Agha taught a studio exploring alternative housing prototypes and the psychology around the idea of the house. Two of her students (now alumni), Hayley Stacy, MIArch, ’20, and Alex Balog, MArch, ’20, wanted to look at the city as a house, examining how it provides options for eating, sleeping, and hygiene, especially among the most vulnerable populations.

“How do you design a house outside of the normative structure of society, and outside centers of power and economics?” Agha posed to her students. Agha wondered how her studio could produce a cultural installation that also transforms into a shelter—an installation of compassion.

During winter term, Stacy and Balog began researching the habits of the unhoused and transient communities in Eugene.

“We were investigating squatting in our group,” Stacy explained. With a team of graduate and undergraduate students in the School of Architecture & Environment, they looked at how the city of Eugene activated the resources available to the unhoused population; where and when unhoused folks are sleeping; shelter capacity; and food banks. Interior architecture graduate student Amicia Nametka became the project manager, and undergraduate architecture student Joshua Fox, who was a certified welder for several years, became site manager.

The group developed design interventions for The Dining Room site, and the project was slated to be completed in July 2020. When COVID-19 caused shutdowns in March, the project slowed, but never stopped. In the spring, Agha had to return to Belgium and Stacy and Balog graduated in June and passed the project forward.

“We developed a strategy where even though we have to stay home [due to COVID-19], we’re still able to pass these drawings along to the younger students,” Balog said.

With continued guidance from Agha from afar, as well as another Design for Spatial Justice Fellow Cory Parker, Nametka and Fox moved the project forward with the help of a handful of student volunteers, working out a budget, specs, site limitations, safety protocols and labor laws, all under the Center for Disease Control’s new rules for interaction during a pandemic. They received a grant from Holden Center and partnered with Freedom by Design, a nonprofit design-build program within the American Institute of Architecture Students, which brought in undergraduate architecture student Adam Abusukheila, who is co-director of Freedom of Design with Fox.

Nametka coordinated volunteers and communication with Food for Lane County, and Abusukheila helped with logistics and picking up and delivering materials.

'It’s the goodness in the hearts of all these architecture students of what they can do during COVID, and everyone wanted to pitch in.'

—Menna Agha

“After a few days of being out there on site, it was one of the first times I felt this way, like I needed to contribute something to the city,” said Abusukheila. “It was a rare opportunity to be that close to the unhoused community and feel safe. You have the pleasure of hearing their stories and witnessing their lives." He added, "The exposure was a reality check as a design student. It made me consider a whole new group of people to design for.”

Fox oversaw fabrication and construction, which was mostly done at Brooklyn Street Studios, a Springfield business that donated the space. Pasquarelli Construction, a local contracting company Fox works for, provided power tools and insight. Due to time limitations, the group contracted Unique Metal Products in Eugene to fabricate the sink frame and enclosure.

The design build included the creation of the three fully mobile hoppers, which are 10 feet tall, nine feet wide, and eight feet deep, and can be set up by two people. Attaching an extra sheet of canvas between the hoppers creates an even larger shelter area, especially useful when there are long lines of people waiting to pick up meals. The group upcycled a long bench that had been attached to an exterior wall of The Dining Room to create more seating attached to two new planters, as well as creating benches designed to set within the longstanding large concrete planters with wooden seats. They also cleaned and painted the exterior of the building, including a mural of a city skyline with flowers.

“With the social unrest and the pandemic, we had to find the willpower in a way to continue such a large project through this adversity,” said Fox of working through the summer. Fox says they were driven by the question: What can we do to provide a nice, dignified place for members of the community? At first, the community that uses the site were skeptical of the project says Fox.

“As the project developed, the acceptance and the thankfulness that the people showed us just fueled us on.”

McCarthy said the students showed incredible devotion and tenacity, and earned the respect of the diners, as well as The Dining Room’s neighbors, who also benefited from the beautification of the space.

“The diners didn’t think they were good enough, but they are,” McCarthy said.

Agha wanted her students to learn that the unhoused population has the right to have an experience of dignity in the city they live in. And that to make a difference as a designer and an architect, one doesn’t need to confine themselves to large buildings or traditional single-family housing. Small design interventions—respite from the rain, beautiful greenery, a dry place to sit—can have instant and lasting impacts.

“It’s the goodness in the hearts of all these architecture students of what they can do during COVID, and everyone wanted to pitch in,” Agha said. “These students are jewels.”

Agha is currently building a “The City is a House” website slated to go live in November.